Analysis: New Zealand’s United Nations Security Council Bid.

36th Parallel Assessments – Analysis By Dr Paul G. Buchanan

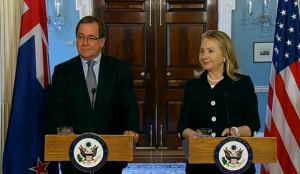

Introduction:On May 24, 2012the foreign ministers of the United States of America and New Zealand met for bilateral meetings after the conclusion of the NATO Summit in Chicago. Afghanistan, Syria and Myanmar were topics of discussion, but the real news was the US’s tacit endorsement of New Zealand’s bid for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council (UNSC) in 2015-16.New Zealand has consistently lobbied for the seat in recent years, but it was not until Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said (at the stand up press conference with New Zealand Foreign Minister Murray McCully) that she “admired” New Zealand’s campaign for the seat that New Zealand’s efforts appear to be rewarded.

Introduction:On May 24, 2012the foreign ministers of the United States of America and New Zealand met for bilateral meetings after the conclusion of the NATO Summit in Chicago. Afghanistan, Syria and Myanmar were topics of discussion, but the real news was the US’s tacit endorsement of New Zealand’s bid for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council (UNSC) in 2015-16.New Zealand has consistently lobbied for the seat in recent years, but it was not until Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said (at the stand up press conference with New Zealand Foreign Minister Murray McCully) that she “admired” New Zealand’s campaign for the seat that New Zealand’s efforts appear to be rewarded.

Prior to this latest bid, New Zealand has held a non-permanent seat in the UNSC three times. The last time New Zealand held such a seat was in 1993-94, so New Zealand diplomats feel that the country is overdue for another stint. In its bid New Zealand is opposing Spain and Turkey (only one country from various diplomatic blocs is selected in each voting round, with 2015-16 seats voted on in 2014), so even with the US endorsement the odds of it gaining the seat are even at best.

The US endorsement of New Zealand’s bid, as well as the timing of it, may turn out to be a double-edged sword. This has to do with New Zealand’s shifting foreign policy orientation and Australian aspirations for a non-permanent UNSC seat in 2013-14 (which will be voted on later this year, and in which Finland and Luxembourg are the other candidates). That means that the two major Anglophone powers in the Southwestern Pacific are vying for non-permanent seats on the UNSC in consecutive years. That might be a hard sell.

The US endorsement of New Zealand’s bid, as well as the timing of it, may turn out to be a double-edged sword. This has to do with New Zealand’s shifting foreign policy orientation and Australian aspirations for a non-permanent UNSC seat in 2013-14 (which will be voted on later this year, and in which Finland and Luxembourg are the other candidates). That means that the two major Anglophone powers in the Southwestern Pacific are vying for non-permanent seats on the UNSC in consecutive years. That might be a hard sell.

US endorsement of New Zealand’s UNSC bid comes on the heels of a warming of relations between the two countries under the National government led by Prime Minister john Key. Relations between New Zealand and the US thawed under the previous Labour government of Helen Clark after years of distance caused by New Zealand’s adoption of a non-nuclear stance in 1985. Even so, under the fifth Labour government New Zealand still clung to its “independent and autonomous” foreign policy, one that emphasized multilateralism, support for the UN and a specialist focus on non-proliferation and human rights issues. Under National that position has been modified to one that prioritizes bilateral relations with the US and Australia and which attempts to straddle the fence between East and West by emphasizing trade relations with Asia and the Middle East while reaffirming defense and security ties with Australia and the US as part of the “Pacific Century” approach adopted by the latter. Evidence of this new approach is seen in the 2010 New Zealand Defence White paper that recommends closer integration with Australian defence forces and the signing of the 2010 Wellington Declaration between the US and New Zealand that re-establishes a full range of bi-lateral military and security relations (to include full intelligence sharing and the resumption of bilateral military exercises). Most visibly, National returned the New Zealand Special Air Services (NZSAS1) to Afghanistan after the previous Labour government withdrew them citing problems with corruption and prisoner abuse, a move that was repeatedly lauded by the US as a major contribution to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission in that country.

These tightened security relationships occur in parallel with New Zealand’s signing of trade agreements with the People’s Republic of China, its membership in the P-4 (Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, Singapore) trading bloc, now serving as the base for the negotiation of the Trans-Pacific partnership agreements involving several Pacific states including Australia and the US, and its negotiation of both general and specific trade agreements with India, Russia and several Middle Eastern countries (including Iran). This two-track approach in which security and trade relations are increasingly diverged rather than converged runs counter to the traditional relationship between security and trade (where security partners tend to be preferential trading partners and vice versa), and demonstrates New Zealand’s interest in pursuing an increasingly Asian-centric trade focus while retaining the security guarantees that come with closer military and intelligence-sharing relations with Australia and the US.

That raises some interesting questions regarding the way in which New Zealand has gone about lobbying for the UNSC seat. China and Russia are both permanent members of the UNSC and undoubtably (albeit quietly) have a say in who occupies non-permanent seats. They are also US rivals. In addition, they are members of the BRIC bloc of rising powers that includes India and Brazil, both of which are seeking permanent seats on the UNSC. It is therefore a matter of conjecture as to whether New Zealand approached any of the BRICs for support in its quest for a non-permanent UNSC seat. If so, public US endorsement of the bid could undermine the support of the BRICs, without which the New Zealand effort is doomed to fail. If not, then its diplomatic skills are clearly wanting and reflect a diminishing understanding of the importance of what can be called “blocmanship:” the ability to navigate and secure the support of different diplomatic blocs within the UN and international community at large.

New Zealand’s Brand Within The UN.

Within the UN, New Zealand is already identified with the so-called CANZ bloc (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) and along with Australia is a member of the Western European and Others Group (WEOG). It is consequently seen as an integral member of the “traditional Western” powers bloc. It is not a member of the 42-member small island state alliance (AOSIS) or the Asia Pacific Group (both of which include many Pacific Island Countries (PICs)), nor is it a member of the non-aligned movement (NAM). This means that even though it is an Oceanic state by geographic definition, it is seen within the UN as traditionally Western in orientation, and therefore responsive to the dictates of larger Western powers. That may have been true during the Cold War, at least until 1985, but for the two decades ending in 2008 New Zealand worked hard to establish itself as an independent Pacific State working within the confines of CANZ and the WEOG to provide a voice for small states in general and its smaller Pacific brethren in particular (say, for example, on the impact of climate change on rising sea levels). With National’s shift in foreign policy that era ended, which makes New Zealand’s Oceanic credentials in the eyes of many less credible today than ten years ago.

Within the UN, New Zealand is already identified with the so-called CANZ bloc (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) and along with Australia is a member of the Western European and Others Group (WEOG). It is consequently seen as an integral member of the “traditional Western” powers bloc. It is not a member of the 42-member small island state alliance (AOSIS) or the Asia Pacific Group (both of which include many Pacific Island Countries (PICs)), nor is it a member of the non-aligned movement (NAM). This means that even though it is an Oceanic state by geographic definition, it is seen within the UN as traditionally Western in orientation, and therefore responsive to the dictates of larger Western powers. That may have been true during the Cold War, at least until 1985, but for the two decades ending in 2008 New Zealand worked hard to establish itself as an independent Pacific State working within the confines of CANZ and the WEOG to provide a voice for small states in general and its smaller Pacific brethren in particular (say, for example, on the impact of climate change on rising sea levels). With National’s shift in foreign policy that era ended, which makes New Zealand’s Oceanic credentials in the eyes of many less credible today than ten years ago.

Thus it would seem imperative for New Zealand to shore up support with important UN voting blocs beyond WEOG before it submits its bid, and in receiving the US endorsement it may well alienate some potential supporters because of their specific conflicts with the US or opposition to US and European domination of the UN in principle. This includes the Pacific Island Forum, South Pacific Conference and Melanesian Spearhead Group, which if not voting blocs within the UN certainly wield influence on their member states within AOSIS, the Asia-Pacific Group and the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) group when these engage in UN voting.

The Helen Clark Factor.

An interesting sidebar to New Zealand’s diplomatic efforts in the UN (or lack thereof) is the presence of former Prime Minister Helen Clark as the head of the UN Development Program. The position is the second most important in the UN and many observers have picked Clark as an eventual UN Secretary General. It could be assumed that Ms. Clark would support the New Zealand bid in principle, although it is possible that the re-orientation of New Zealand foreign policy after her departure from the Prime Minister’s office has made her less enthusiastic about its current role in the international community. Given her power and influence, it may be the case that if she is supportive of the bid, that will translate into votes in favor of New Zealand from countries with which the UNDP works closely, including Oceanic states. But if she decides that there might be an appearance of conflict of interest in her voicing support for the New Zealand bid, than she would likely choose to remain on the periphery of the negotiations leading up to the vote. If her primary concern is about her chances for future appointment as UN Secretary General, then whether or not she is genuinely supportive of the New Zealand bid will likely take a back seat to calculations about the balance of votes in 2012 and beyond (Secretary General Ban-Ki moon’s current term expires in December 2012). Add in the fact that Secretary General appointments must have the approval of the five permanent UNSC members (all of whom have a veto), and Ms. Clark’s calculations may indicate that a more agnostic position on her part with regard to the New Zealand bid is the most prudent course of action, at least until (or if) New Zealand returns to its independent and autonomous foreign policy orientation.

Australia and New Zealand’s UNSC Bids Problematic.

The timing of New Zealand’s bid is also problematic. Australia is lobbying hard for a non-permanent seat on the 2013-14 UNSC, and follow-up selection of New Zealand might be seen by some countries as a case of too much Antipodean presence in too short a period of time. This is especially true because New Zealand’s foreign policy shift under National now squarely aligns it with Australia on security matters, which in turn has become the US’s foremost ally in the Southern Hemisphere and is rapidly on the way to becoming the US’s most important security partner in the 21st century now that the UK is in relative decline (at least when it comes to projecting and sustaining force deployments abroad). Countries that would otherwise vote for New Zealand as an independent Oceanic, small country representative (even if a member of the WEOG bloc) now must take into account the fact that it is no longer acting in the independent fashion that it once did, and that it in fact has aligned itself quite closely with Australian and US interests in the South Pacific and beyond. This may not sit well not only with the BRICs or other Latin American, African or Asian countries disinclined to toe the US line on international affairs. It also may not secure the support of important Oceania countries such as Fiji, which is the subject of official travel sanctions on the part of New Zealand, Australia and the US as a result of the 2006 military coup and which may not wish to see such a strong Antipodean influence within WEOG and the UNSC (Fiji has recently joined Vanuatu as the second PIC member of the Non-Aligned Movement and has cultivated closer diplomatic, economic and military ties with China (and to a lesser extent Russia) under its “Looking North” policy, thereby signaling a shift away from its traditional orientation towards the WEOG in international fora).

In addition, the back-to-back sequencing of the Australian and New Zealand UNSC non-permanent member bids suggests a lack of diplomatic coordination between the two countries. It should be obvious to Canberra and Wellington that, for the reasons outlined above, such a sequence would be problematic at best and could undermine both bids with the result being that at least one of them ends up unsuccessful. It is therefore an open questions to whether the Antipodean neighbors consulted on the timing and sequence of the bids and if so, what rationale caused each of them to continue with their campaigns in spite of the obvious diplomatic conundrum created by their doing so.

Although Australia has relatively small opponents in its quest for the 2013-14 WEOG non-permanent UNSC seat, both Finland and Luxembourg have reputations for relative independence in foreign affairs and have lobbied hard for selection. Thus, even though there are two seats open in the 2013-14 selection round, Australia’s chances of securing the seat are by no means assured even if it has US support, because if nothing else Finland and Luxembourg are seen as less likely to slavishly follow the US lead in UNSC voting. For New Zealand the problem is the same but worse. As a member of WEOG it is now is seen as one of the more US-supportive members of that bloc, but without the strategic importance and diplomatic weight of the Australians. It also is competing with Spain and Turkey for the 2015-16 WEOG non-permanent UNSC seat. Although Spain’s reputation has been diminished by its ongoing economic troubles, Turkey is a regional power on the rise, a bridge between the Islamic and Western worlds, and an example of an Islamic state successfully mediating between national religious and secular interests (to say nothing of an important interlocutor in Middle Eastern conflicts). It is consequently a formidable candidate for the 2015-16 non-permanent UNSC seat, especially because it has exhibited an increasing degree of independence from US and European diplomacy at a time when these are being called into question in other parts of the world.

Why Has NZ Deployed An Open Quest For US Support.

The question therefore remains as to why the timing of the New Zealand bid and why the open quest for US support? Mrs. Clinton’s remarks at the press conference that followed her meetings with Mr. McCully were remarkable for their indelicate tone. In proclaiming admiration for the way New Zealand “ran its campaign” the Secretary of State implied that the US position was a reward for New Zealand’s change in foreign policy stance and its support for US endeavors in places like Afghanistan. This makes it appear as if New Zealand has been obsequious in its attempts to curry favor with the US, which would not matter except for the small issue of its previous reputation as an independent player and honest broker in international affairs. Add to that the Australian bid for a non-permanent UNSC seat in the year immediately preceding New Zealand’s and the possibility of a successful campaign becomes more problematic. Even if Australia fails in its bid, New Zealand’s close association with Australian and US interests may turn out to be counter-productive in light of the other candidacies involved and the lukewarm reception to its overtly pro-US orientation on the part of important states such as those encompassed in the BRICs.

The question therefore remains as to why the timing of the New Zealand bid and why the open quest for US support? Mrs. Clinton’s remarks at the press conference that followed her meetings with Mr. McCully were remarkable for their indelicate tone. In proclaiming admiration for the way New Zealand “ran its campaign” the Secretary of State implied that the US position was a reward for New Zealand’s change in foreign policy stance and its support for US endeavors in places like Afghanistan. This makes it appear as if New Zealand has been obsequious in its attempts to curry favor with the US, which would not matter except for the small issue of its previous reputation as an independent player and honest broker in international affairs. Add to that the Australian bid for a non-permanent UNSC seat in the year immediately preceding New Zealand’s and the possibility of a successful campaign becomes more problematic. Even if Australia fails in its bid, New Zealand’s close association with Australian and US interests may turn out to be counter-productive in light of the other candidacies involved and the lukewarm reception to its overtly pro-US orientation on the part of important states such as those encompassed in the BRICs.

New Zealand may believe that its expanding network of non-Western trade partners allows it to ameliorate concerns about its pro-US orientation and demonstrates that it can bridge the divide between contending great powers as part of a strategic balancing act that continues to show overall independence in foreign affairs. That may be true, but the bottom line is that the UNSC is a security-focused international body, not a trading bloc. That means that it deals specifically with critical and contentious security issues such as the civil uprisings in Libya and Syria. The pressures placed on non-permanent UNSC members at such times are great and often contradictory, and involve a mix of incentives and disincentives of a pubic and private nature offered by the permanent members in pursuit of their often contrary agendas with regard to any specific issue. In that light, New Zealand’s attempts to straddle the fence in its security and trade relations could prove detrimental should it be successful in securing a non-permanent UNSC seat given the balance of power amongst the permanent UNSC members. In other words, its overt pro-US security orientation within the UNSC could elicit contrary responses on the trade front if the US position is opposed by the likes of China and Russia. If it opposes US resolutions or fails to fall in line with US voting preferences in the UNSC it may find itself once again subject to a cooling of relations with its most important security patron. Thus, New Zealand could lose even by winning the campaign for the 2015-16 UNSC non-permanent seat, something that should be factored in along with the other issues mentioned when the final stages of the campaign begin in earnest next year.

New Zealand will likely not prosper in its bid for a 2015-16 UNSC non-permanent member seat. If Australia is successful in its bid for the 2014-15 seat, then the likelihood that New Zealand will be awarded a seat the following term is very low. If Australia fails in its bid, then New Zealand’s chances for selection improve, but its candidacy remains in doubt due to the diplomatic and strategic issues outlined above.