Weekly Analysis: Managing Corruption in the South Pacific

Analysis and Forecast – By Dr. Paul G. Buchanan.

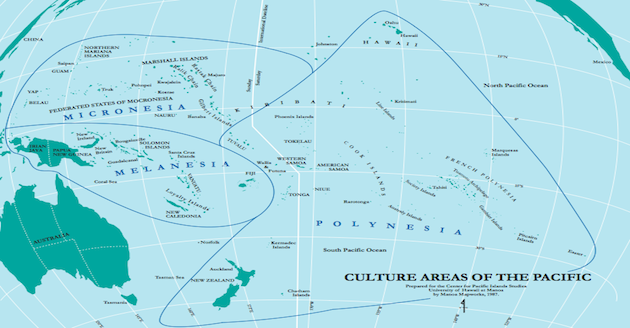

Although it is unfortunate to say so, corruption is a major feature of South Pacific life. It is pervasive, endemic, often culturally rooted but now aggravated by the presence of external actors intent on securing material or political advantages within the region. According to Transparency international, the anti-corruption agency, all South Pacific nations save Australia and New Zealand rank low on transparency scales (10 being high and 1 being abysmal), to the point that there is not a single Pacific Island Country with a 2011 score higher than 4 and most scoring between 2.1-3.3 on the TI scale.

Although it is unfortunate to say so, corruption is a major feature of South Pacific life. It is pervasive, endemic, often culturally rooted but now aggravated by the presence of external actors intent on securing material or political advantages within the region. According to Transparency international, the anti-corruption agency, all South Pacific nations save Australia and New Zealand rank low on transparency scales (10 being high and 1 being abysmal), to the point that there is not a single Pacific Island Country with a 2011 score higher than 4 and most scoring between 2.1-3.3 on the TI scale.

The entrenchment and extension of corruption in recent years comes after decades of anti-corruption efforts, the signing of a number of international anti-corruption conventions by several Pacific Island states (for example, the UN Convention against Corruption–UNCAC), the creation of numerous national and regional anti-corruption agencies and repeated promises made by national governments, the Pacific Island Forum, South Pacific Conference and other region bodies to advance the cause of good governance and social transparency. Ironically, foreign aid efforts may have increased rather than decreased the incidence of corruption in recipient countries. Whatever the causes, the issue in the South Pacific is not whether corruption exists or can be eliminated. The issue is about how to manage it.

There has been much discussion about what constitutes “corruption.” The UN notes that “within a human development and human rights framework we need to explore the idea that corruption is, at least in part, something dependent upon context. Given these conditions… (it accepts) the broadly accepted definition of corruption as ‘the misuse of entrusted power for private gain’ with proviso that confusion may result where individuals and groups occupy a range of roles, and that the power with which they are vested with may come from a number of sources.”

The UN definition of corruption, using a human development conceptualization of the term, includes usurpations of legitimate government such as by military coup d’ etats and infringements of political liberties such as the detention of opposition leaders. The assumption is that anything that interferes with the unfettered right to political expression is a corruption of the democratic ideal. This stretches the definition of corruption beyond reasonable use, as coups, torture, terrorism (be it state or non-state) imprisonment and other forms of politically-motivated coercion, while deplorable, often are not a product of corruption but of ideological zealotry, political belief, and authoritarian notions of what constitutes the “proper” society. Thus, although corruption may be involved in instances of political usurpation or repression, it is not synonymous with it. That being said, practices such as vote-buying are clearly the corrupt dark side of electoral regimes, including several of those in the South Pacific.

Cultural relativists seek to narrow the definition so that traditional gift-giving (koha) and exchanges of favors are excluded. In practice, narrowly-construed definitions of corruption serve to justify a myriad of “traditional” practices in which inegalitarian, non-transparent and unwarranted by merit favors are exchanged and influence is peddled. Often times these practices are institutionalized as “cultural” traditions that serve to reinforce ascriptive hierarchies rooted in family bloodlines or clan, ethnic or regional ties. The difference between traditional gifting and other shows of respect versus corruption lies in the expectations involved. Gifts are tokens of appreciation or respect in which favor is not procured or demanded; corruption is rooted in expectation of favors forthcoming.

Corruption is the purchase or exchange of material, social, or political favors, be it collective or individual, outside of established legal norms and universal standards of conduct.

There was always going to be a problem when attempting to impose Weberian standards on pre-modern patrimonial societies with relatively “shallow” colonial histories. The tyranny of distance and geographic accident combined to delay the exposure of South Pacific, especially Melanesian, cultures to the modern world. When modernity did arrive it often involved brutal colonial administrations that superimposed new forms of arbitrary authority on traditional hierarchies, thereby exacerbating pre-existing divisions while creating new ones. All of this led to a region in which, with some few exceptions, the authority and effective reach of central governments, or what can be called “state capacity,” was limited in geographic scope and lacking in enforcement capability beyond administrative centers. This syndrome continued after the regional wave of independence in the 1960s and 1970s, and remains evident in the rural-urban dichotomy that characterizes many Pacific Island societies, particularly in Melanesia. Specifically, the ability of national governments located in capital cities to effectively enforce their authority in their country’s interiors is problematic at best even if the political will to do so is strong–and that is not always the case.

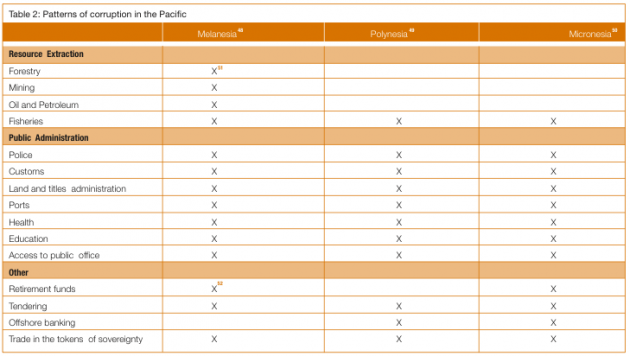

According to the UN Development Program (UNDP), South Pacific sectoral corruption includes the police, customs, land and titles administration, mineral and petroleum extraction, forestry, fisheries, ports, health, education, retirement funds, tendering, trade in the tokens of sovereignty (passports, internet domain names), offshore banking and access to public office .

Broadly speaking, corruption can be economic, political or security in nature. Economic corruption involves business practices and the administration of economic assets. Political corruption involves the manipulation of representation for private gain. Security corruption involves the use of non-use of security forces for opportunistic or particular rather than universal reasons. Since 9/11 the incidence of security corruption such as in the black market provision of false identities by public officials or the sale of legitimate passports to non-citizens, as well as in the provision of off-shore banking facilities, has decreased markedly. However economic and political corruption remains pervasive for both internal and external reasons.

It should be noted that traditions of clientalism and patronage play a hand in the extension of corruption, but are not the same as it. Virtually all forms of politics, be they authoritarian or democratic, involve trade-offs between competing interests, the cultivation of personal networks and the exchange of mutual concessions or compromises. In fact, collective action in general is often associated with clientalism and patronage within collective agents as well as between them. Here the distinction is made between these practices and the use of money, social status or office to secure unwarranted individual or collective gains. The demarcation point between “legitimate” clientalism or patronage and corruption is often hazy, particularly in societies in which these practices overlap with traditions of gifting for social advancement purposes. The South Pacific is a region in which this overlap is wide-spread.

In the last two decades the incidence of corruption has increased due to what can be called Push and Pull factors. “Push” factors are those that are intrinsic to a group or individual, in which personal circumstances or accepted custom and practice facilitate corruption. “Pull” factors are extrinsic to the individuals or groups but nevertheless exert magnetic pressure on them to behave in corrupt ways (for example, financial inducements to public officials by foreign firms seeking privileged access to land title, tax concessions or regulatory loopholes). These pressures can be systemic (such as the impact of the competition between the PRC and Taiwan for votes in international fora, or the Japanese purchase of votes in the International Whaling Commission), regional (such as the Melanesian-Polynesian division within the Pacific Island Forum) or domestic in nature (where, for example hereditary title often is accompanied by material benefits unconnected to the performance of public duties).

The entrance of Asian competitors in the wake of Australian, Canadian and US opening of mineral, forestry, gas and oil exploration ventures has led to a market-driven free-for-all in which bribery, fraud and other forms of corruption flourish.

UNDP Pacific Corruption Table – Author Manuhia Barcham, see link below.

One area where the overlap between corruption, clientalism and patronage occurs is in public bureaucracies, both national and regional, particularly in the management and distribution of foreign aid. Due to its particular geographic and environmental characteristics, the Pacific Island Community is very much aid dependent for the provision of basic services above and beyond emergency assistance. Health, education, pollution control and a number of other public goods can only be provided via the provision of developmental assistance by foreign donors. The sums involved are quite large and have given rise to an “aid bureaucracy” encompassing national nor regional agencies. Unfortunately, some of these bureaucracies have become bastions of nepotism and other forms of ascriptive favoritism that have seen the misuse of foreign aid funds as well as waste and fraud, all to the detriment of those who are supposed to have their quality of life improved via such assistance. Thus the subject of foreign aid, particularly from extra-regional donors as well as Australia and New Zealand, has become a thorny diplomatic issue in the measure that donors demand better accounting and transparency in the administration of aid on the part of recipient countries.

The structure of opportunities in the market of corruption offers strong incentives for short-term maximizers of interest. There are efficiencies in the corruption market, but there is also more uncertainty due to the political conditions as well as the particular economic and social environment in which they operate (and which facilitate corruption). Absent countervailing disincentives, it is rational for self-interested actors to pursue advantage in this market. Over the long-term, once market share is carved out and tenured, these same actors have strong incentive to support institutional frameworks that enforce equitable competitive conditions. This is most clearly seen in the economic realm, although it also true for the political and social markets of corruption. The key to managing corruption therefore rests on structuring short and long-term opportunities in order to incentivize moves towards enforceable institutional transparency in all of its dimensions. This will have to be a sequential process in which potential short and long-term gains are counter-balanced by all collective agents.

In sum, the South Pacific has, for reasons both internal and external to it, seen an increase in corruption over the last two decades. The trend is set to continue in the absence of a unified desire by the Pacific Island Community to stamp it out. For the moment the best that can be hoped for is the management of corruption, such as in the security field, so as to provide the basis for more comprehensive anti-corruption efforts in the future should the political will and enforcement capability increase throughout the region as well as in individual member states.

Futures Forecast: Corruption will remain a salient feature of South Pacific life for the short to medium term, until such a time as market forces as well as government authorities cooperate to better manage its incidence and scope.

See Also: Video Interview: Glenn Williams IVs Paul Buchanan On How Corrupt Is The South/West Pacific

Selected Links:

- Islandsasiabusiness.com – Pacific South East Asia Perform Poorly In Corruption Perceptions Index

- OJS.lib.byu.edu – Pacific Studies Article

- CHL.anu.edu.au (pdf)

- Eprints.whiterose.ac.uk (pdf)

- UHPress.hawaii.edu (Article)

- UNDPpc.org.fj – Corruption In PICs (pdf)

Lead Image Source:

UNDP – Corruption in the Pacific report (pdf page 9)

Original Citation: Larmour, Peter, (2006) “Culture and Corruption in the Pacific Islands: Some Conceptual Issues and Findings from Studies of National Integrity Systems” Asia Pacific School of Economics and Government – Policy and Governance Discussion Paper No. 06-05, Canberra.