Fiji represents the latest iteration of a “top-down” transition from authoritarian to elected civilian rule. “Top down” regime transitions are those where the outgoing authoritarian regime controls the process by which elected government is installed, including the timing and terms of elections. The process is usually marked by two things: limitations on the ability of opposition groups to organise and have their messages heard in a measure equal to military-backed “official” or “continuity” parties; and the election of a government that favours the interests of the coalition underpinning the authoritarian regime (ostensibly in the interest of stability).

That is what has happened in Fiji. The outgoing military bureaucratic regime crafted the electoral framework and a new constitution under which the election was held and the entering government will operate. It used a mixture of divide and conquer and carrot and stick approaches to the opposition and public at large, and it maintained a firm grip on all aspects of the campaign. Former dictator Voreque “Frank” Baimimarama’s Fiji First Party won a clear majority in the 2014 elections with nearly 59.20 percent of the vote. Baimimarama and his authoritarian Attorney General, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum (the main author of the new constitution and electoral rules), were the first and third favourite candidates amongst voters, and Fiji First candidates occupied most of the top twenty spots in terms of voter preference.

As a result, Fiji First will control 32 seats in the new 50 member parliament, whereas the second placed party, SODELPA, which received 28.20 percent of the vote, will have 15 seats. The National Federation Party, with 5.50 percent of the vote, will have three seats (none of the remaining six parties garnered more than 3.2 percent of the vote and are not represented in parliament). That gives Fiji First and Mr. Baimimarama the dominant hand in forming the first elected government since 2006. Just one seat short of a 2/3 parliamentary majority, it will be able to rule alone and pass legislation at will.

However, unlike previous top-down regime transitions, the Fijian case has a number of atypical features. The first is that, unlike many regime transitions in which constitutional reform is on the agenda, the authoritarian-crafted constitution will remain in effect, including clauses that restrict freedoms of association, speech and movement. Second, Mr. Baimimarama has repeatedly stated that he will not work with the opposition parties and would have preferred to have won all 50 parliamentary seats in order to better implement his policy agenda. He sees the parliamentary opposition more as window dressing rather than a vehicle for feedback and critique. This runs against the norm of top-down transitions, where initial post-authoritarian elected governments attempt to form broad coalitions or reach across the aisle in order to achieve cross-partisan consensus on policy.

That is of interest because in doing so the Fiji First government appears to be emulating the basic features of the People’s Action Party (PAP) in Singapore. This may appear at first glance to be surprising because the PAP regime in Singapore is a “soft” one party-dominant electoral authoritarian regime, not a democracy. But Mr. Baimimarama and his advisors (both foreign and Fijian) have clearly studied previous instances of top-down regime transition and may yet opt for the Singaporean model of governance: one with strong central government control over most aspects of political, social and economic life, which uses its dominant position to hold regular, yet controlled elections as a legitimating device for continued rule. Since both countries are relatively small island states, the parallels are not as far-fetched as one might think.

Of course there are significant differences. Singapore is a multi-racial advanced capitalist state that is both a major world port and global financial hub. It has a superlative GDP, high literacy rates and health indexes, and low unemployment and crime rates. Fiji is a largely bi-racial hybrid society (combining pre-modern and modern features) with a mix of subsistence and export agriculture, small-scale mineral, water and other primary good exports, with a significant reliance on services (mostly tourism). It has a low GDP, relatively high rates of literacy, a fair bit of petty crime in urban aras and medium to low health indicators. It has significant unemployment.

Nevertheless, if one compares Singapore at the point of independence and the installation of the first PAP government in 1965 with Fiji in 2014, the differences begin to narrow. Both countries had histories of ethnic and political strife prior to the advent of the current government. Both are former British colonies, and both are relatively resource poor when it comes to natural attributes. It is for these reasons, based upon Singapore’s success as transforming itself into an ultra modern nation-state, that the Fiji First government might consider it to be a model template for Fijian development over the next decades. if nothing else, the Singaporean political model might prove attractive to Fijian elites, who have already embarked on a course to put in place a “guarded” democracy as the first post-authoritarian regime.

Prime Minister Baimimarama’s and Fiji First’s goal may extend beyond “guarding” a new democracy and towards establishing the basis of long-term one party dominant electoral authoritarian rule. In order to do so the Fiji First government must succeed at two things: economic growth and stability; and political legitimacy. With regard to these two requisites, it has certain advantages to begin with. When Singapore gained independence it had little by way of an economic base other than the port traffic derived from its strategic location at the eastern entrance to the Malaccan Straits. Beyond that, the city-state was a relative backwater in which traditional kampung society coexisted uneasily with a post-colonial mix of brothels, opium dens, labor-intensive manufacturing and subsistence agriculture in a topography marked by tropical jungle, swamps and the diseases endemic to them.

Singapore, 1965.

Forcibly pushed out of the Malay Confederation because of its insistence on more autonomy for its largely ethnic Chinese population, Lee Kuan Yew and his foundational PAP cohort had little by way of economic prospects or political legitimacy. In fact, the early years of their rule was marked by ethnic tensions leading to deadly race riots in the late 1960s. This adverse combination led the PAP elite to embark on a societal disciplining campaign marked by severe authoritarian limitations on individual and collective freedoms coupled to a state-managed project of economic development organised around attracting foreign capital in non-traditional economic areas.

Singapore, 2014

In comparison, Fiji is in a relatively better position. Most of the “societal disciplining” occurred under the military-bureaucratic regime and is not needed except as an occasional corrective on isolated instances of social or political defiance. The Fiji First government enjoys widespread legitimacy due to its decisive electoral victory. Although Fiji has stagnated economically in recent years, it appears to be on the cusp of a rebound thanks to infusions of Chinese and Indian capital in non-traditional sectors. Fiji also has significant strategic location in its favour, as it is the hub of Southwestern Pacific transshipment routes, which include a waystation for the Southern Cross fiber optic cable connecting the US to Australia and New Zealand as well as financial and telecommunications providers from around the Pacific basin and beyond.

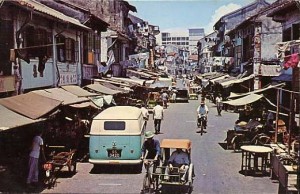

Suva street scene, 2014

In each instance foreign capital was and is instrumental in developing the country and sustaining the regime. In Singapore Western capital led the way, which has been followed by Chinese and other Asian investors (in property and financial services, particularly). In Fiji the curtailment of Western developmental aid after the 2006 coup paved the way for the entrance of Chinese and other Asian capital unconcerned with issues of democratic governance and very concerned with market stability and guaranteed returns (be it material or in terms of influence projection).

In Singapore national elections are held at regular intervals and opposition parties are permitted to organise and campaign. But the gerrymandered system is designed to favour the PAP overall, which has resulted in successive parliaments dominated by large PAP majorities and a small and powerless opposition minority. Even some of the opposition parties see themselves more as tokens than real contenders, in a variant of the 1960s Brazilian experiment with “yes” and “yes sir” parties under the military-bureacratic regime of the day (but without the overt military involvement in governance). As for Fiji, the foundational election of 2014 gives the Fiji First party a PAP-like advantage over its opponents, one that can become enshrined and reinforced if Mr. Baimimarama and colleagues emulate, mutatis mutants, the actions of the PAP during the first two decades of its rule.

For Fiji to emulate Singapore economically it will have to import what the Singaporeans call “foreign talent.” That is because the indigenous skilled labor pool in Fiji is too small to facilitate growth in non-traditional value added productive sectors. But that is exactly what Singapore has done, and Fiji does not have the parallel concern with importing foreign unskilled or semi-skilled labor that Singapore does. So Fiji can pursue a Singapore-style development model by using immigration policy and local labor market demographics to good effect.

For any of this to work, the Fiji First elite have to share the unshakable conviction and ruthless determination that characterised the PAP leadership in the early days of their rule. First generation regime leaderships are usually the most earnest in projecting their preferred future vision of the nation (given the struggles they have been through). In different ways, both the PAP and Fiji First inherited situations that required committed leadership dedicated to achieving their respective visions of national development. Focused political leadership unmolested by the intrusions of a fully empowered opposition is decisive in this model, and that suits the Baimimarama style of governance. Here the political dominates the structural, but it remains to be seen if Mr. Baimimarama is the Fijian equivalent of Lee Kuan Yew, or whether his inner circle is the equivalent of that of the now Minister Mentor of Singapore back in the days when he ruled.

It is nevertheless possible that Fiji, which has direct experience with Singaporean investors tied to the PAP regime, may see in Singapore a model for its future. It will not be able to replicate it entirely, but in terms of one party dominant political features and state-managed economic orientation, it could well prove to be the most attractive alternative given that democracy in Fiji has never delivered on its promises. It may displease Western powers, civil rights advocates and the local opposition that Fiji not return to the preferred combination of democratic governance and free market capitalism, but Mr. Baimimarama has already made clear, in the years after the 2006 coup, that his governments no longer look to the West for examples and support.

Given that backdrop the Singaporean way might be seen by the newly-instlled Fiji First government as the model for the Fijian future, if not economically then at least politically.