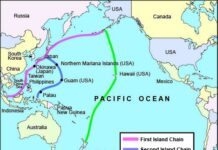

Weekly Analysis: RAMSI in Transition – Towards Indigenous Security?

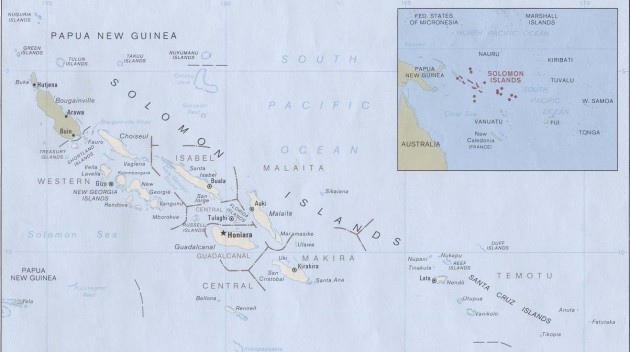

RAMSI is a 10 member coalition of Pacific Island Forum countries engaged in peace-keeping and state-building. It was initially deployed to the Solomons in July 2003 in the wake of prolonged ethnic conflict after a coup in 2000. It deployed in response to an invitation by the Solomon Islands government, then under siege, and continues to operate at the request of the government, which appears happy with the partnership.

RAMSI is a 10 member coalition of Pacific Island Forum countries engaged in peace-keeping and state-building. It was initially deployed to the Solomons in July 2003 in the wake of prolonged ethnic conflict after a coup in 2000. It deployed in response to an invitation by the Solomon Islands government, then under siege, and continues to operate at the request of the government, which appears happy with the partnership.

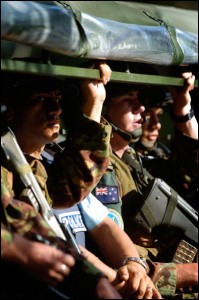

Image: RAMSI deployment to the Solomon Islands. Photo by Jason Dorday, courtesy of Scoop.co.nz.

RAMSI is a good example of modern multilateralism at work. Led by Australia and seconded by New Zealand, it has three “pillars:” security, economic and governmental capacity building. Among these objectives, the imposition of law and order took precedence in the first years of the intervention, as it was a pre-condition for the establishment of governance institutions and economic development programs. In this week’s dispatch we shall examine the evolving security dimension of the RAMSI mission. Analysis of the other two pillars will follow in future reports.

RAMSI is a good example of modern multilateralism at work. Led by Australia and seconded by New Zealand, it has three “pillars:” security, economic and governmental capacity building. Among these objectives, the imposition of law and order took precedence in the first years of the intervention, as it was a pre-condition for the establishment of governance institutions and economic development programs. In this week’s dispatch we shall examine the evolving security dimension of the RAMSI mission. Analysis of the other two pillars will follow in future reports.

Image: RAMSI deployment to the Solomon Islands. Photo by Jason Dorday, courtesy of Scoop.co.nz.

As in Afghanistan and Iraq, the recruitment and training of indigenous security forces in the Solomons was complicated by the the heavily armed nature of society… and by primordial clan and tribal divisions.

The RAMSI security mission has two components: military intervention and policing. According to RAMSI, “The primary role of RAMSI’s military contingent, known as Combined Task Force 635, is to provide support and assistance to RAMSI’s Participating Police Force (PPF) as it works to strengthen the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force. In the initial period following RAMSI’s arrival in 2003, the key role of RAMSI’s military was to provide protection for the PPF and other parts of the Mission, necessary due to the serious law and order situation and the large number of illegally-held weapons present in the Solomon Islands community at the time. The key focus of RAMSI’s military now is to deter destabilising elements within the country, and support RAMSI’s Participating Police Force efforts to strengthen the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force capacity to maintain law and order and provide a stable security environment.”

The military aspect of the mission has largely been successful. The original division-sized force was able to re-establish control of the country on behalf of the Honiare-based central government. Thousands of weapons were turned in under an amnesty program, and opinion polls show that the majority of Solomon Islanders feel safer and more secure as a result of RAMSI’s ongoing intervention in pursuit of improved human security as well as in countering criminal and other anti-social behavior. The process has not been easy, with the military contingent having to return in force after the outbreak of collective violence in 2006 (mostly directed at ethnic Chinese after the election of Snyder Rini as Prime Minister), and with RAMSI suffering two deaths and the wounding of several dozen personnel during the course of the nine year intervention. At present there are approximately 160 troops divided into a Headquarters complement and three platoons (one from Australia, one from New Zealand and one rotating between Papua New Guinean and Tongan infantry) serving four month tours with CTF 635.

As the RAMSI military component has been reduced in the measure that law and order has been restored, the Police component has taken centre stage.

An important factor that mitigates against a full PPF withdrawal is its utility as a professional development program for Pacific Island Country police personnel. Although under-represented in leadership roles within the PPF, Pacifika officers constitute a large majority of those deployed on RAMSI duties. Hundreds of police officers from an array of small island states such as Nauru or Micronesia (to say nothing of Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, among others) have participated in the PPF, with funding and institutional support coming from the PIF. Using a regional variant of British-style community policing standards to develop a “best practice” organizational culture within the RSIPF, Pacifika personnel have honed their own operational and cultural skills. Patrols by Pacific Island Country officers paired with RSIPF officers are considered to be a particularly successful strategy that benefits officers and the community alike. Given that success amid ongoing concerns about the potential for violence in the event of a complete RAMSI security withdrawal, is is likely that the PPF will continue to operate within the Solomon Islands for the foreseeable future and that a Pacifika component will remain in the PPF even if Australian and New Zealand officers are withdrawn.

Professionalising local security forces involves three tasks. One is ideological, one is disciplinary, and another is corporate. The ideological dimension involves securing the loyalty of local security forces to the central government. The disciplinary dimension involves learning the concept of appropriate and commensurate force, including weapons fire and physical self-control. The corporate dimension involves developing an autonomous sense of organizational identity and self-governance (non-politicised), which involves the promotion of objective and merit-based managerial standards and professional criteria for retention and promotion.

Parallel promotion of governance institutions, to include public bureaucracies as well as political parties, electoral systems and parliament, are key to securing the loyalty of local security forces, although such necessities as regular wages and job security are valuable in securing the material bases of consent in the ranks. The peaceful 2010 elections show progress on the former, while PPF-managed recruitment and retention schemes with established pay grades and promotion paths help reinforce professionalism and meritocratic practices within an increasingly self-reliant security bureaucracy.

… there are concerns that withdrawal of the RAMSI security component will be followed by a resumed wave of disorder and primordial violence.

One external factor that works in favor of the RAMSI transition towards indigenous security is the growing presence of foreign investors. Foreign investment requires an institutional and regulatory framework that, given the competing interests, is perceived to be procedurally autonomous, self-governing and objectively neutral in approach. Central to this is the universal application of the rule of law, including its application to macroeconomic and sectoral regulatory frameworks as well as stability on the streets. That requires a fair enforcement capability, which involves the police, courts, customs, immigration and taxation agencies. There is therefore an external push for the development of a strong indigenous security and enforcement capability in the Solomons that runs in parallel with the increased levels of foreign investor interest in the country.

Should the RSIPF prove incapable of fulfilling a naturally professional law enforcement role, then the field is open for other solutions in the form of private security contractors (PMCs), many of which offer military and para-military services. A particularly well situated PMC is Fiji Defense Logistics.

Futures Forecast: RAMSI will continue to transition towards a devolution of security command and control to indigenous agencies, most importantly the RSIPF. The transition will be slow and gradual, and even if the military component is completely withdrawn, ongoing PPF presence is expected to continue for the next several years. In the measure that civil disorder does not break out in the face of this limited draw-down of foreign security personnel, the onus for stability will increasingly fall on domestic governance institutions aided by RAMSI’s non-security state-building efforts. Barring an unforeseen government collapse, the prospects for domestic security over the next few years are good.

RAMSI Security Stability Score: 7.5 (good) (Stability Score ranges from 1 (low)-10 (high) based on the degree of institutional capability exhibited.

Selected Links.