Influence Operations.

Influence operations, also known as influence peddling, are normal and legitimate tools of states as well as non-state actors such as private firms, non- and international governmental organizations. They are focused on the old adage “how to win friends and influence people” in pursuit of organizational objectives, be these diplomatic, economic, military or cultural in nature. The purpose is to create a favorable impression of a state, firm or agency in the mind of a target entity, be it the general public or selected subsets of it, particularly key interlocutors (agencies as well as individuals) whose decisions impact on the fortunes of the influencing agent or organization.

Influence operations are the stock and trade of private sector lobbying and government outreach programs in foreign states. They include everything from wining and dining of potential business clients, partners or government decison-makers, providing transportation and accomodation to people of influence, staging cultural and artistic events, contributing to political parties and causes, organizing charities, creating education exchanges, donating goods and services, establishing media outlets and generally doing “favors” or good deeds in a target country, region or economic sector. The goal is to create a favorable impression of the influence peddler on the part of targeted entities and people in order to alter the narrative about the influencer in ways that are positive and profitable for it.

Influence operations are a well established part of foreign policy. Institutions like the Alliance Francaise, various US agencies and institutions like the Fulbright Commission, AID and Peace Corps, cultural promotion and friendship societies funded wholly or in part by foreign governments such as Confucious Institutes or Jewish Councils, business associations like the NZUS Council and American Chambers of Commerce–all of these organizations are in the business of promoting home country interests via various methods of exchange. The provision of developmental aid is another form of influence operation. A good example is China’s “checkbook diplomacy” in the South Pacific, where it provides no-or low-interest developmental loans to island states or gifts infrastructure projects to recipient countries as gestures of goodwill. The list of entities and countries that engage in influence peddling is not limited to powerful states or large business interests, and the cumulative impact of their operations is significant in shaping local perceptions of the international order.

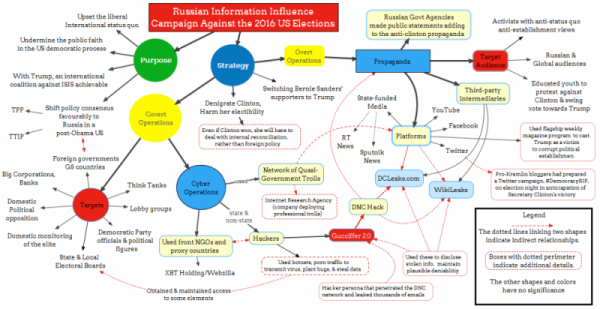

Influence operations are most often overt in nature. However, there are instances when they may be used covertly to good effect. Russian use of social media to influence the tone of US campaign coverage (by among other things, placing political adverts and event invitations on platforms like Twitter and Facebook) is a classic instance of attempting to alter the narrative in order to influence the backdrop and lead-up to the elections. The use of so-called “disinformation campaigns,” in which false news stories are seeded throughout social and mainstream media outlets, is one prominent form of covert influencing (as well as giving birth to the phrase “fake news”).

The limits on influence operations are determined by local statutory and regulatory frameworks governing the domestic behavior of foreign agents. Some countries have relatively loose rules governing the activities of foreign influencers while others adopt more restrictive approaches to what can aand cannot be done by foreign agents on domestic soil. This includes what is acceptable when it comes to permissable monetary rewards, exchanges in kind or other forms of inducements provided by influence peddlers to others. In some South Pacific countries, decision-makers expect to be compensated for their time and interest in an influencer’s pitch regardless of the outcome. However, what is seen as koha or tribute in one context is seen as bribery in others, so influence operators must be keenly aware of where local mores draw the line at what is legal or illegal, legitimate or illegitimate when it comes to exchanges of favors.

Targeted Intervention.

Targeted intervention is a more contentious subject but in reality is just an extension of influence operations. Whereas influence operations focus on “softening up” targeted entities by altering general narratives about the influencer in ways that are more favorable to it, targeted intervention concentrates on securing specific outcomes within a targeted entity. This can be done by placing people in key decision-making positions, planting stories in compliant media or putting money into causes or individuals with the intent of securing a desired outcome in their fields of influence. Targeted interventions are conducted by businesses as well as political actors and state agencies.

Targeted interventions can be done overtly or covertly. Placing people in political parties with the intent of having them elected into office is one example of overt targeted intervention, unless the loyalities or political objectives of the person are disgusied or hidden. Donating to election campaigns is another overt form of intervention. Placing people in targeted businesses or public agencies, or engaging in third party financing of negative (or positive) advertising campaigns, are covert forms of intervention in specific fields of endeavour.

Targeted intervention becomes contentious when it is done by foreign actors, particularly states but to include businesses, in order to advance their agendas vis a vis a a sovereign entity. This has been a subject fo considerable concern in the South Pacific, where commerical interests in extractive industries have been accused of intervening covertly using both coercive as well as financial means to disrupt opposition to their activities and to secure favorable environmental, health and safety regulations from local government in spite of that opposition.

Here again, Russian involvement in the 2016 US elections is illustrative. Russian intelligence is alleged to have hacked into the email servers of the Democratic presidential candidate and Democratic National Committee. Selected emails from these accounts were bundled with fake emails purportedly from the same authors and delivered to the whistle-blowing organization Wikileaks, which promptly published them. These were then picked up by mainstream media outlets in the US and covered extensively in the weeks leading up to the November ballot. The furore over the content of the emails gave ammunition to the Republicans and put the Democratic candidate on the defensive. Although it is unclear to what extent the negative cobverage of the email “scandal” contributed to the Democrat’s defeat, with the margin of victory boiling down to 60,000 votes (out of 130 milliion cast) in two swing states, it is possible that the targted intervention by Russian hackers had a role to play in the outcome.

Even more directly, US intelligence has alleged that the Russians also attempted to tamper with elexctronic balloting in 21 states. These efforts were thwarted by US counter-intelligence measures and led to quiet threats of reprisals, but the larger point is that the attempted manipulation of ballots by the Russians is a clear example of targeted intervention.

To be fair, the US has a long history of targeted interventions in foreign countries, up to an including electoral manipulation and material support for insurrections and coups d’etats. The point here is to stress that many forms of targeted intervention fall far short of these extreme measures and in fact often preclude such extremes from happening.

Intelligence gathering.

Intelligence gathering is the process of acquiring information on targeted entities without their knowledge or consent. This can occur overtly or covertly and is conducted by private agencies as well as governmental organizations and states. The purposes of intelligence gathering are to determine intent, motivation, patterns of behaviour, organizational charcteristics and capabilities, resource bases and Open source intelligence gathering such as that provided by 36th Parallel Assessments uses public records, secondary sources, personal interviews and scholarly analyses to provide indepth appraisals of specific situations. Open source intelligence gathering is also conducted by state intelligence agencies, think tanks, research institutes, and a variety of international, governmental and non-governmental organications. For example, economic and political officers in embassies spend most of their time tasked with drawing up assessments of current events in their host countries.

Covert intelligence collection is the use of surreptitious means to gather sensitive information about target entities. The targets can be military, diplomatic, economic or social in nature (say, family dynamics within dynastic regimes). Covert intelligence takes three main forms: technical intelligence (TECHINT) gathering (e.g. thermal imagery, acoustic, radar and seismic monitoring; signals intelligence (SIGINT) gathering (e.g. phone wiretaps, computer hacking, fiberoptic cable “bugging,” telemetry intercepts, decryption programs); and human intelligence (HUMINT) gathering (where human agents are sent into the field to gain both startegic and tactical insight into the behaviour of targeted entities as well as provide context to them). HUMINT comes in two forms: official cover, where the intelligence agents is provided official protection (“cover”) via embassy or other governmental affiliation formalized in the issuance of a diplomatic passport (thereby granting some level of immunity from criminal prosecution): and non-official cover (NOC), where the intelligent agent operates outside of the protections of diplomatic representation by posing as something other than a government agent, for example, as an academic, business person, charity worker, etc).

Be it overt or covert in nature, intelligence gathering is often conducted in concert with or in support of influence operations and targeted interventions. This is because intelligence gathering hekps identify the best courses of action in any given context, including points of strength and weakeness in targeted entities. The closest overlap is between intelligence collection and covert targeted influence operations, where the former identifies the targets of intervention as well as the best means by which to achieve specific results. Conversely, influence operations tend to be more public in nature and due to their relative exposure to accusations of being potential fronts are often deliberately walled off from intelligence operations.

Conclusion.