Analysis & Forecast: Paris Coughs, Papeete Gets The Flu

Analysis and Forecast – By Dr Paul Buchanan.

A stone thrown into a pond sends concentric ripples to its far reaches. When they hit the shore the ripples are much wider than those close to the plunge. There is a political analogy to this: decisions made at the core often have a magnified effect on the periphery, especially when it comes to the relations between a large power and its overseas possessions.

A stone thrown into a pond sends concentric ripples to its far reaches. When they hit the shore the ripples are much wider than those close to the plunge. There is a political analogy to this: decisions made at the core often have a magnified effect on the periphery, especially when it comes to the relations between a large power and its overseas possessions.In another post-colonial legacy, France’s budgetary cutbacks within the context of European Union crisis and austerity have had a repercussive effect on French Polynesia. This will be seen in the impact the upcoming French elections have on political stability in the “French Overseas Country/Collectivity” (the first round is held on April 22, with a run-off vote two weeks later) . The Left-Right divide is compounded in French Polynesia by pro- and anti-independence political parties and nearly complete fiscal dependence on the French.

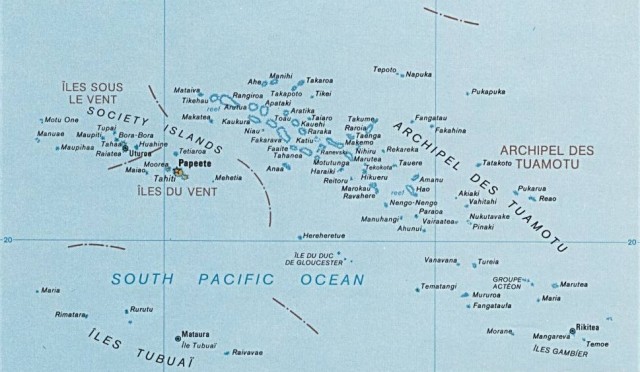

French Polynesia covers five archipelagos (Marquesas, Society, Gambier, Australs and Tuamotu) ranging from 15-35 degrees south and 135-155 degrees west. The political capital, Papeete (located at 17°34′S 149°36′W / 17.567°S 149.6°W), is home to the French Pacific Fleet. In another post-colonial irony, French Polynesia has suffered from steady economic decline after the end of French nuclear testing in 1996 (the Pacific territories being the replacement for testing grounds lost after Algerian independence in 1962). Reduction of labor and material associated with the “nuclear economy” has not been compensated by tourism or traditional export growth (for example, black pearls and vanilla).

The French Polynesian government, a parliamentary democracy with a French-style public administration with French and Polynesian staff, has the power to raise taxes and operate its administrative apparatus as it sees fit. This includes responsibility for local financial and economic affairs, customs and taxation, tourism, transport, agriculture, fisheries, public works, health, primary and secondary education and social welfare as well as control over its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), air and sea transport links, telecommunications and postal services and internal security. French Polynesia belongs to several regional organizations dedicated to environmental and transportation matters, and negotiates its regional cooperation agreements with countries grouped in the Pacific Island Forum (to which it is an associate member) and the South Pacific Conference (of which it is a member). Through its appointed High Commissioner, France controls immigration, defense and policing, justice and law, monetary policy, tertiary education and foreign affairs. Increasingly, it has also held the major share of public purse strings.

French Polynesia elects two deputies and one Senator to the French Legislature. Instead, what was left was a society marked by the rapid transition from subsistence to service economics (which meant, among other things, that cultivation of local crops and fishing were rapidly replaced by service provision to the nuclear economy), an over-large, white and creole staffed public bureaucracy whose lifestyles exceeded those of public servants in the homeland and far exceeded those of indigenous polynesians, leading to gross socioeconomic disparities and social tensions caused by unemployment and class differentials. These are exacerbated by an educational system taught only in French, and a racial hierarchy that sees Europeans (mostly French) constituting the bulk of the socio-economic elite, European-Polynesian Creoles occupying the comprador middle class and serving as the political elite, with indigenous peoples populating the working and underclasses.

The end of the nuclear economy displaced much local labor, which given the decline of traditional economic activity left a large pool of unemployed.

France spends approximately US$1.6 billion a year on the territories, with 17 percent going to government administrative expenditures and local investment (largely in infrastructure). 83 percent of the allocations from the central government are directed at defense, education, public service salaries and pensions. Over the years financial dependence on France has increased as revenues from taxation on exports has decreased as a percentage of total inputs, with an estimated 60 percent of GDP derived from French transfer spending. As a majority private enclave economy dominated by foreign interests, French Polynesian tourism revenues have been repatriated abroad much more than they have been reinvested locally, and the government tax take on these revenues is not sufficient to fund public goods and services. Thus French loans have served as bridges over French Polynesian government budget gaps, which are ever-widening.

French Polynesia is administered under provisions of Article 74 of the French Constitution. Under an Organic Law passed on 27 February 2004, French Polynesia’s degree of political autonomy was strengthened as “an overseas country within the French Republic.” The position of President of French Polynesia was created and a new electoral system for the Assembly was established. The Assembly consists of 57 members elected by simple majority vote, with a 15 member Council of Ministers serving as the Cabinet. The President is elected by a simple majority vote of the Assembly for a five year term. Assembly members also serve five year terms. French Polynesia uses its own flag, seal and anthem in conjunction with the French national symbols.

Whatever French intentions may have been with regard to devolving government powers to locally elected authorities, the result has been constant political instability. Resting on wafer-thin majorities and vulnerable to motions of no-confidence, twelve governments have ruled since 2004, and the divide between separatists (pro-independence) and autonomists (anti-independence, but not as subservient as French Loyalists) is very much alive. There is a residual bitterness in some parts of the community over the nuclear legacy, particularly with regard to the lack of compensation for physical dislocations and illnesses caused by the testing program. Concurrently, ideological weakness and political nomadism aggravate the instability problem, as there is much party-swapping and tactical shifts between highly personalized political camps. Parliamentary gridlock is the norm, recently evident in the lengthy delay in approving the 2011 budget. Modern concepts of legitimate authority, as well as the nature of relations between colonial, national and local governance are not well understood within parts of the indigenous society, so demagogic and populist appeals as well as patronage ties hold strong sway in political practice.

Political Assessment:

The personal and political tension between the long-time President (and de facto strongman), autonomist Gaston Flosse, and pro-independence leader and current president Oscar Temaru has been at the heart of the post-2004 instability…

Sarkozy’s position on French Polynesia rests on his programmatic commitment to decentalisation of political decision-making along with the imposition of fiscal austerity regimes in a market-driven environment. His approach is based on his approach to regional government at home, to the point that his High Commissioners in recent years have come from and returned to prefectures in France (French Polynesia is one of 27 regional governments, of which five are overseas territories). Nevertheless, ongoing political instability in the Polynesian territories is a serious impediment to thes achievement of these goals. In 2010 Sarkozy lamented that “French Polynesia deserves serious elected leaders and not a vast comedy where enemies of yesterday become the allies of today.” “At a time when everyone should mobilise their energy to face the current crisis, this chronic instability is intolerable for those (French) Polynesians who are suffering. I will therefore initiate this year a reform of the electoral system and of the institutional mechanisms in order to guarantee more stability to elected majorities and therefore to give more capacity to envisage political and public actions in the long term”, he said.

In the Prime Minister’s annual New Year speeches, Sarkozy has made repeated calls on all French overseas communities to “take charge of their own economic destiny” by generating their own economic self-reliance…

In the meantime the French government is withholding US$60 million loan to French Polynesia. It argues that it wants the money directed at infrastructural projects and investment. The French Polynesian government wants to use the loan to pay public sector salaries and pensions, which are in arrears in some areas. The impasse will not be resolved until after the general elections. In addition, the French government has announced plans to dis-establish 177 teaching positions and require teachers of French Polynesian origin to serve terms teaching on the mainland. Although many of the dis-established teachers are mainland French and can find work at home, local teachers resist moving to France. As a result, the proposal has been met with calls for strikes, to include a general strike in solidarity with the educators.

Security Assessment:

It is against this backdrop of deep and overlapped divisions and instability that the French elections will impact on French Polynesia, at least with regard to its governance. Because voters in French Polynesia will be voting on the composition of the central government rather than their own (since elections in French Polynesia are scheduled for 2013), the outcome will be very indicative of what the immediate future will hold in terms of politics. In the 2007 general elections, the result was very tight and favorable to Sarkozy. That year the French Polynesian turnout was 69.12% in the first round of the election and 74.67% in the second round (the French electoral system is a two round process by design). French Polynesian voters put Sarkozy ahead of Socialist Ségolène Royal in both rounds of the election, with the second round going to Sarkozy 51.9% to Royal’s 48.1%. Temaru backed Royal and Fosse backed Sarkozy.

Although the presence of the 5000 troop French naval garrison and French gendarmes mitigates the possibility of violent clashes and generalized disorder, these tensions are likely to see deepening political paralysis…

If Sarkozy wins in French Polynesia as well as on the mainland then Fosse’s forces will be strengthened and will likely move to topple the Temaru government and implement the reforms demanded of it. This will result in open conflict which will likely require the use of force to suppress pro-independence and anti-French sentiment, but even that is a short term solution that does not address the underlying antagonisms that are at the heart of the French Polynesian malaise.

Futures Forecast: If the Socialists win the majority of French Polynesian vote in the April 2012 elections, then the Temaru government will ramp up its sovereignty claims and resist mainland government attempts to impose fiscal austerity on the public service. This will occur regardless of the outcome on the mainland. But if Sarkozy wins the general election then there is a strong probability that tensions between the Temaru government and the central administration will worsen to the point of rupture and possible intervention by the French state in administering French Polynesian affairs by executive fiat backed by force. If Sarkozy’s Union for a Popular Movement Party (UMP) wins a majority in French Polynesia, then it is likely that the Temaru government will be subject to a vote of no-confidence led by Fosse and his political allies. That is likely to be successful and will result in a more compliant French Polynesian government when it comes to negotiating with the mainland although it will not stop the back room intrigue in the lead up to the 2013 elections).

Stability Index: 3 (poor). (Stability indexes are scaled from 1 (low) to 10 (high) based on institutional continuity and efficiency). In this case ongoing economic stagnation within a context of ongoing political instability makes for a low aggregate score.

Selected Links:

- Pacific Scoop – New Paris Envoy Pledges To Solve Tahiti’s Crises Problems

- Politicalresources.net/france-pol

- Mfat.govt.nz/Countries/Pacific/French-Polynesia

- Islandsbusiness.com

- CIA.Gov World-Factbook (French Polynesia)

- BBC Country Profiles (French Polynesia)

- NZ Trade and Enterprise – Doing Business In French Polynesia (pdf)

- Australia Department of Foreign affairs – French Polynesia Brief