36th Parallel Assessment

Introduction.

Extending roughly from O degrees South to 60 degrees South and 70 degrees West to 160 degrees West, the South Pacific has traditionally been marked by the tyranny of distance: tiny populations on small land masses widely dispersed across a huge expanse of ocean far from metropolitan sources of power and development. As opposed to economies of scale, where unit costs are lowered as productive outputs are integrated, attempts to promote regional integration in the South Pacific have led to a phenomenon known as the “diseconomies of isolation:” the costs of bringing together small, dispersed, resource-poor island nations far outweigh the benefits accrued from their integration, to the point that doing so results in a net loss of investment capital region-wide. Worse yet, infusions of capital and aid (since 1970 the region has received the highest levels of developmental aid per capita in the world) have not led to sustained economic growth or development but instead have promoted a culture of economic dependency that can be justified on humanitarian grounds but not by market logics. This syndrome, called the “Pacific Paradox” by the World Bank in 1993, remains as the fundamental conundrum of the South Pacific in the early 21st century.

MENU:

Introduction | History | Political Architecture | Political Futures Forecast: | Economic Architecture: | Economic Futures Forecast: | Securities Architecture | Securities Futures Forcast

Historically thought of as resource poor and little more than stopping points on the way to somewhere else, the South Pacific began to assume a regional identity as a result of de-colonisation and the end of World War Two. Combined with anti-colonial struggles in the region and elsewhere, the creation of the UN, where equal votes are granted all member states regardless of size, was of particular importance in forging national and regional identities among South Pacific island states. Even then, differences between Melanesian (in the mid-Southwest Pacific Rim), Micronesian (on the lower Northwestern Pacific Rim) and Polynesian (comprised by a geographic triangle extending from Hawai’i in the North to Easter Island in the Southeast and New Zealand in the Southwest Pacific) have made attempts to forge a strong and unified regional identity problematic to this day.What has changed is that in the late 20th and early 21st centuries industry and commerce have conquered distance in the form of transportation, telecommunications and extractive technologies, which has the potential to open up the region to new actors as previously inaccessible resources become available to investors. Coupled with changes in the geopolitical environment resultant from the end of the Cold War and post 9-11 security environment, this has brought the South Pacific to the world and set the stage for it being an arena for strategic competition in the years ahead.

In this overview 36th Parallel Assessments will focus on the regional architecture of the South Pacific and its sub-sets (economic, political and security networks).

In this overview 36th Parallel Assessments will focus on the regional architecture of the South Pacific and its sub-sets (economic, political and security networks). Although it will address the role of Australia, France, New Zealand, the US and other external actors as pertinent, the focus is on the relationships between South Pacific Island states (PICs). In order to frame the discussion, the concept of regional institutions and regional architecture need to be introduced.

Broadly considered, regional institutions fall into two categories: policy-making institutions and policy-implementation institutions. Some institutions perform both functions, although in practice most policy-implementation is done by specifically charged and functionally defined agencies that answer to, or interface with, policy-making agencies. The key to success of regional institutions is to promote functional cooperation at both levels, otherwise policy is made in name only. Regional architecture refers to the complex of institutions within a given geographic area. Generally classified as those that address issues of governance, economic development and security, regional institutions are made up of a latticework of overlapped networks and agencies. Although many are formal institutions, a number of informal institutional arrangements are also included in the architecture. For example, although the Pacific Island Forum (PIF) is a formal institution that holds annual ministerial meetings that set general policy direction for the 16 member compact, much of what “gets done” in practical terms occurs on the sidelines of the meetings, where state actors, non-government organizations and private parties quietly negotiate matters of mutual interest. Likewise, bilateral and multilateral aid and diplomatic relations overlap with the activities of the PIF when it comes to implementing the UN Millennial Development Goals and decennial “Pacific Plan” for better governance and growth. This makes for some opaqueness in terms of jurisdictions and responsibilities among the agencies involved.

This assessment is a 36th Parallel internal discussion document and it is not meant to provide guidance or offer a definitive statement on the subject.

History.

Beginning with the creation in 1947 of the South Pacific Commission, later renamed as the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), the South Pacific offers an excellent example of post World War Two efforts to promote multinational integration in the lesser-developed world. The region saw some of the earliest instances of regional development projects, substituting for the pre-war bilateral ties between Pacific island nations and their colonial or post-colonial patrons (the UK, France and the US in particular).

After the era of independence (1962-70), the UN, foreign country aid agencies (particularly those of Australia and New Zealand) and private non-governmental organisations (NGOs) assumed the lion’s share of regional developmental efforts. For better and worse, the last fifty years has seen the South Pacific used as a testing ground for the UN and other international organizations when it comes to providing development assistance and policy-oriented integration schemes under multilateral aegis. The record is mixed, but the architecture that has emerged as a result of these efforts is extensive, overlapped and multi-faceted, if not entirely effectual.

The SPC was, in essence, an effort by the United States, France, the UK, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand to create an anti-communist regional bloc under the Cold War “containment” doctrine that would ensure strategic denial to the USSR in the South Pacific. As such it responded more to the strategic interests of the Great Powers and their regional allies rather than as a developmental platform and political forum for the island countries themselves. The Netherlands abandoned the SPC in 1962 and the UK, after temporarily withdrawing in 1996-97, permanently withdrew from the SPC in 2005.

The SPC channeled developmental assistance from the Great Powers in response to Cold War concerns, particularly perceptions of Soviet inroads (such as the establishment of an embassy in Port Moresby in 1976 that closed a few years later). Such development projects were episodic, short-term and used as a form of leverage or patronage in order to secure Pacific Island Country (PIC) cooperation with Western strategic goals. This led to tensions between island governments and their patrons, particularly over the issues of post-colonial interference and nuclear testing. As a result, and coinciding with Fijian independence, the South Pacific Forum (now called the Pacific Island Forum or PIF) was created in 1971. It includes overseas protectorates of the US north of the equator (the Marshall Islands and Federated Republic of Micronesia), with France, the UK, the US and other foreign-held island territories having associate or observer status while remaining members of the SPC. Australia and New Zealand remain in the PIF. French Polynesia has associate member status in the PIF, while Timor Leste has observer status (Timor Leste has applied for membership in both the PIF and ASEAN, with its chances for admission much higher in the former because ASEAN states do not wish to assume the aid burdens associated with Timorese underdevelopment).

The SPC, which originally had policy-making and policy-implementation functions as part of its charter, reverted to research, planning and technical assistance for programs and policies developed by the PIF Secretariat. Implementation of PIF Secretariat policy is done by the Council of Regional Organisations in the Pacific (CROP), which includes ten regional organisations: Fiji School of Medicine (FSM), Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS), Pacific Islands Development Programme (PIDP), Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Agency (SPREP), South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC), South Pacific Board for Educational Assessment (SPBEA), South Pacific Tourism Organisation (SPTO) and the University of the South Pacific (USP). The SRC’s activities are divided into Land, Maritime and Social Service Divisions, whereas the PIF focuses on development and economic policy; trade and investment; political, international and legal affairs; and corporate services. The range and scope of the services rendered is broad, with health and literacy campaigns and disaster relief (in conjunction with foreign parties) being mainstays of SPC work. In general both organizations focus on trade, aid and governance issues. Even so, there appears to be a disconnect between the SPC and PIF mandates and missions, leading to overall institutional weakness, which undermines the architectural integrity of the regional organization.

The end of the Cold War saw a decline in Western interest in South Pacific Affairs. The US downscaled its aid and diplomatic representation outside of its territorial possessions while various Asian countries, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in particular, increased their aid, diplomatic, investment and trade presence. The Japanese cultivates the relationship primarily because of its interest in PIC votes in international whaling disputes. Taiwan and the PRC seek to secure PIC votes on the issue of Formosa’s diplomatic representation. South Korea, along with the others, sought to gain preferential access to regional fishery stocks. The diplomatic competition between the two Chinese states has somewhat eased in recent years while their economic involvement has increased, with the PRC now leading Taiwan with regard to investment and trade (and has the largest diplomatic presence of an foreign state in the region). In fact, China is now the third largest source of aid and second largest source of investment in the PIF, trailing Australia and the US in the former and Australia in the latter.

The emergence of the PRC as a potential super-power has altered the Oceanic geopolitical environment, particularly on its Southwestern fringe.

The architecture of the Southeastern Pacific is much less developed because the island territories are all controlled by continental states. The UK, US, France Ecuador and Chile hold possession of island territories, including the iconic Galapagos (Ecuador), Easter Island (Chile) and Bora Bora, Noome’a, Papeete and Tahiti (France). Here mother country law and treaty agreements apply in the first instance, although all of these possessions save the Galapagos are linked to the PIF and SPC via diplomatic courtesy and UN funded development schemes.

Political Architecture.

The PIF is the pre-eminent political institution in the South Pacific and the ministerial meetings that follow on the annual Leadership Forum talks are considered to be the primary agenda-setting forum for the region. The Pacific Plan (now halfway its first implementation) is supervised by the Secretariat of the PIF and administered by the SPC via the ten CROP agencies and international partners.

Important South Pacific Organisations:

The alphabet soup approach to policy implementation has led to an entrenched bureaucracy (headquartered in Suva although Fiji’s membership is suspended) that has become a political actor in its own right.

Headquartered in Port Villa, Vanuatu, the MSG includes a sub-regional trade group under the name of the MSG Trade Agreement signed in 1993, which has expanded to cover 180 articles free of fiscal duty traded between the members on a most favored nation basis. Recently the MSG has counter-balanced the PIF suspension of Fiji (2009) by holding its own leader and ministerial meetings. Foreign actors and private parties are turning to the MSG as the first point of contact with regard to commercial ties and investment in Melanesia, where an extractive resource boom has been underway for two decades. In doing so these actors, most importantly the PRC, have by-passed the PIF, SPC and CROP networks.

The rise of the MSG saw a response in the creation of the Polynesian Leaders Group (PLG) in 2011.

Other than participation in the PLG and associate member status with the PIF, French Polynesian territories are not fully integrated into the regional political architecture. This is because although politically autonomous in terms of government selection processes and domestic policy, they are administered by the French state and ultimately respond to its foreign policy interests. This was most evident in French nuclear testing, which sparked major protests throughout the South Pacific and among other things resulted in covert French bombing of the Greenpeace Ship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbor in 1985 (which led to a decade long diplomatic row between France and New Zealand). Today French foreign policy objectives in the Southeastern Pacific are limited to free passage of goods and services, environmental protection (ironically), anti-crime efforts and intelligence sharing with the US, Australia and New Zealand. Although French possessions, New Caledonia and Vanuatu are more highly integrated into the regional architecture of the SPC, PIF and MSG. This provides France with a window of Southwestern Pacific affairs, if not a means of influencing policy-making in those states as well as regional bodies.

The Galapagos remain a dependency of Ecuador and have no representation in the major regional political forums (although it retains links with a number of environmental agencies that do work elsewhere in the South Pacific). Easter Island, ancestral home of the Rapa Nui people who share genetic lineage with New Zealand and Cook Island Maori, are a Chilean possession and treated as such. Governance and policy is steered from Santiago and administered by representatives of the Chilean state. This has led to tension between Rapa Nui and mainland Chileans that have recently resulted in clashes ended by police repression.

Bilateral and multilateral involvement of extra-regional actors such as the US, Taiwan, China and Japan, along with those of Australia and New Zealand, represent a parallel network of diplomatic ties that competes with the multilateral initiatives with the PIF and SPC. Although these parallel networks and initiatives often overlap with PIF policy objectives, they also have at times undermined the authority of the regional organizations, thereby compounding the problems of internal division within them.

The SPC was, in essence, an effort by the United States, France, Australia and New Zealand to create an anti-communist regional bloc in the South Pacific that would ensure strategic denial to the USSR. As such it responded more to the strategic interests of the Great Powers and their regional allies rather than as a developmental platform and political forum for the island countries themselves. The South Pacific has an extensive but inefficient political architecture due to a mix of factors endogenous and exogenous to the region. These include cultural differences, sovereignty concerns, interference by extra-regional actors, lack of bureaucratic capacity, corruption and political divisions amongst island states. This has led to the creation of distinct sub-groups within the PIF, something that speaks to potentially enduring conflicts between the Melanesian and Polynesian sub-groups that could lead to a permanent fracture of the PIF and its diminution as the lead regional political agency. That will benefit the MSG, which if it continues its rise as a competitive sub-group within the PIF fueled by increased foreign investment capital and diplomatic ties, could end up as the most important regional forum in the years ahead.

Economic Architecture.

Given the diseconomies of isolation extant in the South Pacific, the nature of its economic relations with the outside world are by definition asymmetric. The asymmetry lies in the fact that traditional foreign aid and investment in the region far exceed PIC exports and developmental progress measured in GDP growth, literacy rates and health care indicators. This in turn has led to a central feature of South Pacific trade agreements: the preferred PIC arrangements vis a vis more developed states within and beyond the region (such as Australia and New Zealand on the one hand and the EU on the other) are also are asymmetrical. The reason is structural. As a report by the Institute for International Trade at the University of Adelaide points out, “the classic gains from trade (due to specialization) may be reduced for very small economies in an RTA [Regional Trade Agreement] because the opportunity for gain depends on regional liberalisation exposing a complementarity of the partners’ economies. There is less prospect of two economies being ‘complementary’ if one is much smaller than the other, resource-constrained, and geographically isolated.” (Institute for International Trade, Research Study on the Benefits, Challenges and Ways Forward for PACER Plus, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, 2008, p.55).

PIC’s preference is for trade agreements to exclude tariffs on PIC exports while maintaining them on non-PIC imports. This is designed to overcome the competitive disadvantages structurally embedded by the diseconomies of isolation.

The overall thrust of the approach is to wean the PICs off of dependence on a limited range of commodity exports so as to achieve a more balanced mix of primary good and value add production. The objective, in other words, is to use asymmetrical trade in order to make them viable off-shore export platforms.

Scholarly Article – By Dr Paul G. Buchanan and Kun-Chin Lin:

The approach is premised on the belief that globalization of production of the last two decades has brought the PICs into the global commodity chain. Non-traditional areas such as energy generation and telecommunications offer potentially lucrative areas of investment. But the PICs suffer from the dreaded “lack of capacity:” beyond poor physical resource bases in many PICs, the lack of human capital, skilled labour in particular, makes it very difficult for PICs to direct the flow of investment in pursuit of efficient and managed growth without significant external assistance. Here foreign aid programs are important, because along with the CROP network of regional aid agencies, these engage in the actual capacity building that is a prerequisite for the move towards value-added global commodity production.

Implicit in this model is the notion that with capacity building comes value transfer.

The degree to which bureaucratic sclerosis undermines aid provision varies from country to country and sector to sector (for example, environmental, health and literacy programs vary markedly across the region), but the overall effect is to perpetuate the paradox of Pacific diseconomies of scale. The disjuncture between capability-building seen as labor force up-skilling in pursuit of economic diversification and integration, on the one hand, and foreign aid programs seen as encroachments on sovereignty and self-determination on the other, makes for delicate diplomatic terrain. The more misunderstandings or differences there are between patrons, investors and donors, the less progress will be made on the economic benchmarks outlined in the Pacific Plan and various regional trade agreements (RTAs).

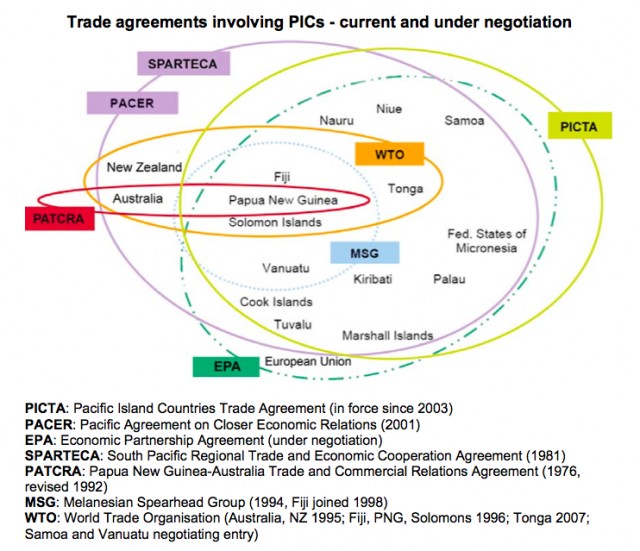

Like its political architecture, the South Pacific economic architecture is an overlapped web of treaties, agreements and bilateral obligations.

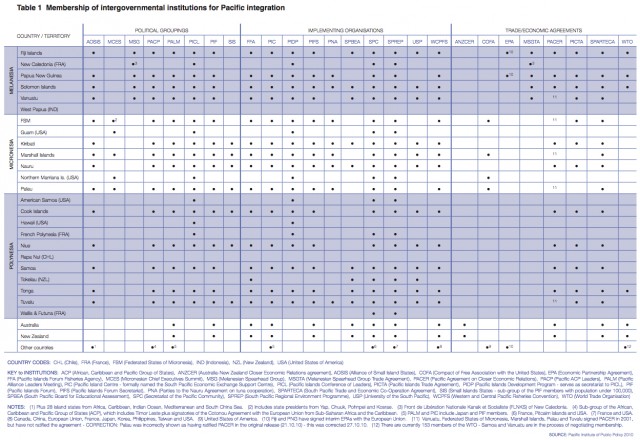

Pacific Islands Countries Trade Agreements – Graph courtesy of Oxfam NZ.

Pacific Islands Countries Trade Agreements – Graph courtesy of Oxfam NZ.See Also 36th Parallel Document: Regional Architecture (raw information resource)

The first regional trade agreement was in fact the bilateral Papua-New Guinea-Australia Trade and Commercial relations Agreement (PATCRA) signed in 1976 and revised in 1992. This agreement, which allows duty-free access of PNG goods to Australia, was less about cross-border trade and more about Australia’s diplomatic relationship with the newly independent PNG, and has since been complemented by subsequent agreements. In 1981 the South Pacific Regional Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement (SPARTECA) was signed. It continues to be the main trade regime for the region, although its position has been partially overshadowed by the Pacific Agreement on Economic Relations (PACER) signed in 2001. Several South Pacific States are members of the WTO, and negotiations for trade relations are ongoing with the European Union (Economic Partnership Agreement EPA) and with Australia and New Zealand in the so-called PACER PLUS talks. The two regionally-specific trade agreements are the those of the MSG (initiated in 1994 and updated in 2007) and the Pacific Island Countries Trade Agreement (PICTA), which includes the Marshall island and Federated States of Micronesia as members of the PIF. Along with the proposed EU EPA, these frameworks do not include Australia and New Zealand. It should be noted that PICTA, which has delayed implementation of a time-table for gradual trade liberalization and tariff reduction between its members, is considered to be a “stepping stone” towards a more comprehensive regional trade agreement in the form of PACER and PACER Plus (which now are negotiating platforms rather than FTAs, and are also delayed in their progress).

There is consensus that until trade relations between the PICs are harmonized (if not entirely liberalized) and their duty and tariff regimes made symmetrical, negotiations with Australia and New Zealand on a more comprehensive regional trade regime will move slowly

Beneath the broader trade regimes mentioned above, there exist a number of compacts regulating aviation (Pacific Islands Air Services Agreement (PIASA), which involves the Association of South Pacific Airlines (ASPA) and South Pacific Civil Aviation Council (SPCAC) as well as the governments of signatory states), fisheries (South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) and the convention on highly migratory stocks WCPFC8), environmental standards (South Pacific Regional Environment Program (SPREP), seabed mineral exploitation (International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN-created program overseeing mining of deep-water seabed resources outside of exclusive economic zones), tourism (South Pacific Tourism Organisation (SPTO)), whaling (International Whaling Commission (IWC), although only Australia, Chile, New Zealand, Peru and the Solomon Islands are South Pacific members) and other common concerns (see the resource page for direct links to sectoral protocols).

There are also numerous professional associations representing and regulating various economic sectors (such as the afore-mentioned ASPA and PADI, the Professional Association of Divers International, which regulates international standards for open water diving and which certifies diving instruction and tours in the South Pacific). It is worth noting that both of these types of association involve non-governmental agencies as well as national state agencies, to include international organizations and private interest groups.

The most serious impediment to achieving the objectives of the regional economic architecture as outlined in the Pacific Plan and other formal declarations is the lack of institutional regulatory capacity. A regulatory institution or agency is only as viable as its powers of enforcement. Regardless of legal mandate, if an institution does not have the ability to enforce standards, rules and procedures, then it is an institution in name only. As in the case of regional political institutions, the South Pacific economic architecture suffers from deficiencies in enforcing universal standards. Poor customs and immigration controls, the absence of policing mechanisms (the largest navy in the region, that of Fiji, has only nine in-shore patrol boats) and the prevalence of corruption or incompetence mean that exclusive economic zones (which are the largest in relation to land mass in the world) cannot be adequately protected nor can legal trade regimes be enforced. This has resulted in a burgeoning black market trade in a wide range of goods and more ominously, the proliferation of criminal enterprises dedicated to mine laundering, arms, drug and people smuggling.

That returns us to the issue of institutional capacity-building, developmental prospects

Lacking a comprehensive strategy to address the three variables in holistic fashion, the South Pacific will continue to suffer deficiencies and inefficiencies in promoting regional economic growth.

Security Architecture.

Security agencies are all those that primarily use coercion, or the threat of coercion, to enforce a status quo or impose an outcome on those undisposed to cooperate or comply voluntarily. These can be divided into law enforcement (Police, Customs, Immigration, Coast Guard, Fisheries, Para-Military Gendarmes and Border Patrol, among others) and military (Army, Navy, Air Force), with both supported by Intelligence services.

A security architecture is the ensemble of security agencies and organizations that work to ensure a peaceful status quo within a given geographic area. Regional security architectures are made of national and international security agencies whose combination results in force multipliers and other synergies that promote efficiency in the regional provision of security and reduce individual burdens in securing the peace in a multinational geographic context.

The present day South Pacific security architecture has its roots in the Cold War. During that time the US, UK and France maintained military control of their respective patches of territory in the region, with Australia and New Zealand serving as military deputies for the first two. As part of this division of labour each of the three big powers conducted nuclear weapons tests in remote atolls until public opinion and improved technologies made the practice redundant and uneconomical (France did not stop testing until the 1990s). The key focus of the Northern Powers was on containing the Soviet Union’s military presence and diplomatic influence in the South Pacific, something that ended in 1990. After the end of the Cold War the UK and US downscaled their regional military presence, with the UK withdrawing completely from the region in the early 200os. During the 1990s the US also diminished its regional diplomatic presence, while France was content to retain a small tripwire force (including a garrison ship) in its former (now semi-autonomous) colonies. For their part, Chilean and Ecuadorean military presence was limited to their exclusive economic zones, which in Chile’s case consists of a (self-proclaimed but internationally non-recognised) triangle that extends from the southern and northern borders of the Chilean mainland 2000 kilometers west out to Easter Island.

During and after the Cold War the US, UK, Australia and New Zealand, along with Canada, operate the Echelon system of electronic eavesdropping (which combines Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) and Technical Intelligence (TECHINT), the former involving electronic eavesdropping on foreign telecommunications and the latter directed towards imagery acquisition). Collection stations in Australia and New Zealand permit global SIGINT and TECHINT coverage by the partnership, a very small percentage of which is directed at the South Pacific. Human Intelligence collection (HUMINT) in the region is parceled out to Australia and New Zealand, (Melanesia in the case of Australia and Polynesia in the case of New Zealand). For its part France engages in intelligence-gathering in its territories and served as a liaison partner to the US and its South Pacific allies. During the Cold War the focus was on monitoring USSR activities in the region. After the Cold War the regional intelligence priority is on irregular warfare, transnational crime and the PRC.

The 1990s and early 2000s saw the US focus its military attention on the Middle East and Central Asia. Its naval forces continued to be focused on the Atlantic Ocean and Middle Eastern choke points, while its land and air forces continued to prepare for the 2.5 Major Regional Conflicts (MRC) scenario by which the US could fight and prevail unassisted in two and a half major regional conventional conflicts. The South Pacific had very little role to play in such planning, and Australia, France and New Zealand were entrusted with militarily “keeping the peace” within their respective spheres of regional influence . The major security concerns for the decade after the Cold War were internal conflicts and sub-national violence rather than inter-state belligerency, with Australian and New Zealand troops deployed on peace-enforcement duties in Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and East Timor during that time frame.

In the 2000s two factors came into play that altered the post-Cold War period of benign security neglect of the South Pacific: The terrorist strikes of September 11, 2001 raised the specter of global irregular warfare, and, the second development was the emergence of the PRC as a strategic rival in the South Pacific.

The concern is founded on three factors. The first is that China is embarked on a significant military upgrade, with an emphasis on shifting from a land-based defense force to a naval and air-led expeditionary force that has the ability to project power far afield. This includes putting into service a retro-fitted Soviet vertical and short lift (VERSTOL) aircraft carrier (which is designed for training purposes rather than combat) and expanding its submarine fleet to 90 boats from its current 65. Although most of the submarine fleet is diesel the Chinese are incorporating nuclear-propelled vessels into service, giving them the ability to extend their combat radius while staying on station longer.

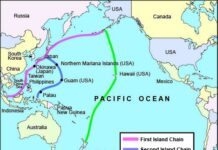

The second factor is the Chinese “three island chain/string of pearls” maritime strategy. The purpose of the three island chain strategy is to effectively ring the PRC with three concentric lines of defense and attack, the first covering the Sea of Japan, East and South China Seas to Indonesia; the second from the Aleutians to New Zealand; and the third from Hawai’i to Tahiti. The string of pearls component is to construct forward naval re-supply bases in foreign countries so that supply and logistics chains can be extended throughout the tiered island chains. China has already signed forward basing agreements with Pakistan and the Seychelles as part of its naval presence in the Indian Ocean and is in discussions with several African countries on similar arrangements (all of this based on its desire to protect mineral resource, forestry and oil supplies from the Africa and the Middle East).

The Chinese have already begun long-range submarine patrols in the South Pacific, reported to be about a half dozen per year. They are suspected of trailing the Chinese fishing fleet, whose nets provide acoustic cover for the diesel boats and which may serve as SIGINT collection platforms.

Given this Chinese emergence as a potential military rival to the US in the South Pacific, the US, Australia and New Zealand, along with France and to a lesser extent Chile, have re-focused their attentions on the trans-Pacific sea lines of communication. The US has announced a major shift in deployments, reversing 50 years of strategic logics by shifting sixty percent of its submarine fleet and five carrier task forces from the Atlantic to the Pacific (the area of responsibility of the Pacific Command headquartered in Honolulu and which includes the US 7th Fleet). The US has also forward deployed strategic bomber squadrons and Los Angeles class attack submarines out of Guam, and is upgrading and facilities to accommodate a Marine light division-sized Rapid Expeditionary Unit and its complement.

Most of the South Pacific island states do not have indigenous armed forces, and instead rely on Australia, New Zealand, the US and France for their protection (for example, New Zealand provides security guarantees for the Cook Islands and for Samoa (the latter based on a 1962 treaty), and both Australia and New Zealand have guaranteed the protection of Nauru, Niue, Palau and the Solomon Islands. France provides for the defense of its territories in Vanuatu, New Caledonia and French Polynesia, while the US has security agreements with the Marshall Islands, Kiribati and Federated States of Micronesia. Chile maintains a small garrison and a naval port in Easter Island, and Ecuador maintains a navy and coast guard presence in the Galapagos.

There are three standing militaries in the PICs: in Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Tonga.

The Republic of Fiji Defense Forces consist of 3500 active duty and 6000 reservists. The majority serve in the First Infrantry regiment made up of 3 infantry battalions, the first two of which have served extensively on peacekeeping deployments in East Timor, Lebanon, Iraq (which was more of a combat mission) and the Sinai. The 300-man Navy operates nine patrol boats (three Australian Pacific and four Israeli Dabur class). It maintains security agreements with Australia and the UK (both suspended as a result of the 2006 coup) and increasingly with the PRC (which now trains RFDF officers in Beijing and stages regular naval port visits and small-scale exercises with the Fijian Navy). In recent months reports have surfaced that Fijian military personnel are being recruited by a Fiji-based defense contractor for duties in Papua New Guinea.

The Papua New Guinea Defense Force (PNGDF) numbers 2,100 soldiers and is divided into land, air and marine units. Originally a component of the Australian Army and then self-organised after independence in 1973, PNGDF troops have served as peace-keepers in the Solomon Islands and have fought insurgents in Bougainville, Buka and and Irian Barat. The PNG maintains security agreements with Australia, Nw Zealand, France, Germany and China (the latter budgetary aid only). The main force consists of two light infantry and one engineers battalion, with the navy operating four Pacific Class patrol boats (supplied by Australia to several PICs under the Pacific Patrol Boat Plan) and two Balikpapan class landing craft. The air force consists of 100 personnel operating 3 helicopters and four light fixed wing aircraft, with VSTOL training provided by Singapore and Indonesia.

The PNGDF suffers from serious internal divisions and a lack of operational capacity, something that Australia has moved to correct via more intensive bilateral education and training exercises. Even so, the reported recruitment of Fijian military personnel for defense contractor work in PNG suggests that military factionalization is serious and potentially de-stabilizing because loyalties within the ranks are seriously divided.

The Tongan Defense Services (TDS) consists of 500 troops, the majority in land forces and the Tongan Royal Marines. It has three Pacific class patrol boats and two light aircraft. Its troops have recently served in Iraq, Afghanistan and the Solomons, and Tonga maintains bilateral security agreements with Australia, New Zealand, India, the US, UK and the PRC (mostly in the area of leadership training, although Tongan troops have also served with US and Royal Marines in Iraq and Afghanistan). The TDS is a participant in defense management and leadership exercises such as the Pacific Armies Management Seminar (PAMS), Pacific Area Senior Officers Logistics Seminar (PASOLS) and Western Pacific Naval Symposium (WPNS). In 2006 TDS troops were deployed to quell riots in Nuku’alofa, but the main focus for the last decade has to prepare for and deploy abroad in support of the US, UN and other allies.

Beyond the extensive network of foreign security coverage of most of the PICs, it is noteworthy to flag the use of Fijian, Papuan and Tongan military forces for internal political and security purposes. This impinges on their professionalism and autonomy, and has led to tensions with Australia, New Zealand and the US when military interventions result in violence (such as the 2006 Fijian coup and the 2012 Papuan military revolt). Possible Fijian military involvement in PNG domestic conflicts has the potential to aggravate as well as extend the problem of military politicization.

The two main trends evident on the military side of the regional security architecture is 1) increased professionalism of the TDS as a result of its overseas deployments and exposure to advanced military operations, and, 2) a shift from a Western military orientation with regards to bilateral training and exercises towards an Asian orientation, with China in particular.

With regards to policing and internal security issues, the PICs are linked together in the Pacific Island Chiefs of Police (PICP), which started out in 1970 as the South Pacific Chiefs of Police Conference. Consisting of 20 members, the PICP includes US and French territories as well as independent island states. Australia and New Zealand are members of the PICP, which is designed to standardize law enforcement procedures, promote cooperation and improve the overall quality of policing in the member states.

The Pacific Island Chiefs of Police (PICP) has working relationships with a number of regional organizations, including the:

- Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS),

- Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC),

- Oceania Customs Organisation (OCO),

- Pacific Islands Law Officers’ Network (PILON)

- Pacific Prevention of Domestic Violence Programme (PPDVP).

The PICP works with the Pacific Affairs section of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and bilaterally with the International Deployment Group of the Australian Federal Police, including the Pacific Police Development Program and the International Service Group of the New Zealand Police.

There been some discussion, most recently voiced by former Australian Prime Minister John Howard at the 2003 Pacific Islands Forum, of creating a South Pacific region police force. This was not the first time that such a concept had been floated, but it assumed a more serious character once it was formally raised as a topic of discussion within the PIF. Unfortunately, questions of sovereignty and disagreements about funding, force composition and timetables impeded progress on the matter, at least within the PIF framework. As a replacement, in 2004 a Pacific Regional Policing Initiative (PRPI) was started in order to standardize and improve police training, logistics and cooperation. Headquartered in Suva and initially funded by grants from the Australian and New Zealand governments, the initiative has also foundered in recent years due to the diplomatic standoff between Fiji and Australia and New Zealand as a result of the 2006 coup and 2009 postponement of elections. In spite of its lack of success the PRPI remains an objective of the PIF and Pacific Plan, so should relations between Fiji and other Forum members improve it is likely that efforts will be made to reestablish it as a security priority.

Several countries in the region are members of INTERPOL, the international police organization: Australia, Fiji, Marshall island, nauru, New Zealand, PNG, Samoa, Timor Leste and Tonga (on INTERPOL activities in the region see this source document).

In spite of cross-regional and international linkages and the various initiatives proffered over the years, regional policing and related internal security operations remain under-developed and non-standardised. Australia and New Zealand continue to push for the adoption of Western (mostly British inspired) professional standards in the region’s police forces, and to varying degrees national police forces have achieved various degrees of professional competence and efficiency. However the police, even more so than the armed forces, have a strong political role in many of the PICs and have been seen in some quarters as tools of particular political interests rather than serving as a commonweal organization serving the public interest as a whole. So long as agreement is not reached on police professional development programs and related areas of cooperation, policing in the South Pacific will continue to be haphazard and sometimes arbitrary. The situation is better in island territories of foreign powers, where central state administrative control has improved the professional demeanor and efficiency of local police departments. As a result, levels of crime are generally lower in these territories than in the independent island states.

The issue of policing, or the lack thereof, is a matter of grave concern given that recent decade have seen strong growth in organized crime activities throughout the region. In part due to the spotty police record and other institutional failures and in part due to the impact of globalization of trade and commerce has had on previously largely isolated island nations, the criminal influx has been focused on 1) establishing new secure shipment routes between Asia, the Antipodes and Latin America; and 2) opening new markets in the South Pacific itself. Coupled with the nexus between irregular warfare groups (such as al-Qaeda) and criminal organizations (mostly dedicated to arms, drugs and people smuggling as well as money-laundering), this poses fundamental problems for the maintenance of regional law and order and runs the risk of turning vulnerable island states into criminal safe havens in spite of the efforts to promote regional approaches to crime-stopping. The situation is particularly problematic in the Southwestern Pacific. The irony is that the promotion of free trade and opening of commercial borders in the South Pacific have unwittingly facilitated the expansion of criminal enterprise in the face of local police forces’ inability to cope with the new security challenges presented by open borders.

Securities Futures Forecast:The regional security situation for the next 6-18 months will be one of flux. Tense civil-military relations in places like PNG and Fiji, the praetorian character of the military in those same countries and ongoing deficiencies in policing through the South Pacific have the potential to see both criminal and political violence on the rise. Sino-US relations will also factor into the mix, as the US strategic re-orientation towards the Western Pacific in the face of growing Chinese influence brings with it the possibility of a regional militarization and/or arms race in which PICs find themselves playing off the two great powers in what amounts to a regional balance of power game.