Monthly Analysis: Managing Political Expectations.

Paul G. Buchanan

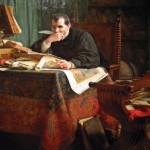

“Niccolo Machiavelli (nello studio)” 1884 oil on canvas. Stefano Ussi (1822-1901). Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome.

“Niccolo Machiavelli (nello studio)” 1884 oil on canvas. Stefano Ussi (1822-1901). Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome.

The Arab Spring and its sequels have tested a few propositions and added new chapters to the study of regime transitions. Whatever the nature of the change (revolutionary or reformist), the subject of managing political expectations continues to get relative short shrift. That is odd because it is a topic pertinent to any form of government that relies on majority support for its continuance in power, and more importantly, for the consolidation of the new political regime itself.

Achieving and maintaining majority political support requires management of public expectations of what is reasonable in terms of demands and what is achievable given the socio-economic and political context of the times. Resource availability, trade dependency, labor force skill base, nature of political representation and a host of other factors influence what are considered to be “reasonable” demands and “achievable” goals at any given point in time.

If individuals and groups concur on what is generally reasonable and achievable, it is easier to manage political expectations. Agreement on specific issues does not have to be uniform or absolute, and instead is the subject of institutionalized conflict resolution mechanisms administered by the state.

The key element in determining what is reasonable and achievable in a particular historical moment is government framing of the issues that condition individual and group approaches to making demands on political authority. Issue framing not only allows the government of the day to define the terms of debate about the specifics on which reasonable demands and achievable objectives are construed. It also allows the government to manage popular expectations as to what is and is not reasonable or achievable.

One major problem for nascent regimes in the Middle East and elsewhere is and has been managing popular expectations of what can be delivered by a sudden move to electoral rule. “Democracy” means a lot of things to a lot of people, from unfettered freedom of expression to free blue jeans and TV sets. Many envision democracy as conferring a panoply of rights unencumbered by responsibility, to include the need for tolerance of others whose views, persuasion or traits are not congruent with one’s preferred worldview.

The rush away from authoritarianism also has a tendency to encourage demagogic promise making on the part of political contenders. More so that in established electoral systems, these promises have little relation to (or bearing on) what can be reasonably demanded on or achieved by the new regime, in part because many of those making the promises have never had experience in government. The syndrome is compounded when the incoming elite has little knowledge of, much less training or skills in the complexities of macroeconomic management, social policy, international diplomacy and trade or a myriad of other areas of government responsibility. Sometimes the best opposition leaders are the least qualified to govern.

The combination sets up the scenario of failed expectations: new political regimes based on popular support often fail to adequately manage expectations so as to give themselves time to learn the intricacies of their position and to establish priorities as to what can be reasonably demanded and achieved. Popular demands for short-term remedies and immediate material gains outweigh the regime’s capacity to deliver on what was promised, much less what was implicitly expected at the moment of transition. This has been evident in Egypt and, with some significant differences in terms of the specifics of what is being debated and the intensity with which it is being contested, in Tunisia as well.

In established democracies the issue of managing expectations has roots not so much in what is immediately promised but in what has been historically delivered. The longer and more deeply embedded the concepts of reasonable and achievable are in the public consciousness, the more difficult it is to significantly alter downwards the terms on which popular support is given. Should democratic governments move to redraw the concepts of reasonable and achievable in order to downgrade or reduce the political, social and economic terms of support, the more likely it will be the non-institutionalized collective conflict will result. That has been the case in Greece and Spain.

The phenomenon can be conceptualized as reaching the limits of popular consent.

Political expectation management involves setting the terms of what is politically, socially and economically reasonable to demand and what the government can be expected to achieve in a given time frame (in election-based regimes usually coincident with government terms in office, although long-term expectations underpin ideological support for the regime as a whole). Governments can trade off lowering expectations on one level while raising them on another (say, by trading democratic participatory rights for economic growth), but the combination must balanced as a social equilibrium.

This is especially hard to achieve in societies that are in some form of transition, be it cultural, demographic, economic, political or in combination. In the Middle East, Africa, East Asia and the Pacific Rim the changes have been many, major and rapid, which makes managing political expectations all the more complex.

The South Pacific combines a mix of mature and new democracies with various forms of autocracy. Popular expectations vary from very limited to quite comprehensive, with deep historical traditions uniquely intertwined with globalizing influences in the contemporary political landscapes of the region.

This makes the specifics of managing political expectations very different from country to country even if the general requirements of satisfying economic, social and political demands and achieving reasonable policy goals remains constant for all governments.

Left to right: Cesare Borgia, Cardinal Pedro Luis de Borja, Niccolo Machiavelli, and Micheletto Corella (secretary to Borja), circa 1500. Author unknown.

Managing political expectations is different than spin doctoring or public relations. The latter are cloaks on policy decisions or are part of image or crisis management. Political expectation management involves issue framing and policy formulation and execution. In order to be effective, political expectation management needs to have a complex grasp of the interplay of cultural, demographic, historical, international and contemporary societal features in a given political context. It needs to understand the threshold of popular support with regards to the provision of public goods and larger distributional and accumulation issues.

Unlike expectation management in other contexts where hype and hope are combined into orchestrated mass anticipation events, political expectation management mainly involves lowering, diminishing, downplaying or soft peddling what can be reasonably expected of government. This reduces or narrows the threshold needed to secure ongoing popular support, which among other things allows governments to provide “surprise” policy rewards when conditions allow for more than what is minimally expected. By defining what is reasonably achievable on reduced terms, governments can anticipate and schedule “bonus” policy outcomes according to their own logics and criteria (for example, in the run up to elections).

Although political expectation management is of most concern to governments, it also has relevance to investors, diplomatic partners, non-governmental agencies and others who have an interest in political stability in a given country. Moreover, interested parties have reason to engage in political expectation management of their own as they engage with governments on matters of mutual interest.

Summary.

Political expectation management is an oft-neglected aspect of governance, particularly in states undergoing major societal transitions. Successfully managing political expectations over time is a key to regime and social stability because it frames what are generally considered to be reasonable demands and reasonably achievable policy objectives by governments. The key to success lies in balancing the political, social and economic aspects of popular expectations so that a basic threshold of majority support is achieved over time.

36th Parallel Assessments provides tailored political expectation management services for governments, non-governmental organizations and private clients.