Nuclear weapons are in the news again, this time because recent satellite photos reveal that China is constructing large nuclear missile silo “farms” in its Northwestern desert regions. This has occasioned alarm in Western security circles and re-focused attention on the concept of nuclear deterrence. This essay will address some of the basic concepts involved in nuclear strategy and deterrence, then offer some thoughts on the contemporary state of play. First, though, a personal anecdote by way of introduction to the subject.

While pursuing my Ph.D. I was a student of one of the US’s original nuclear strategists, someone who had been a targeter during the planning for the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his old age he taught nuclear strategy and wrote several books and articles that outlined the logic of nuclear deterrence that obtained from the end of WW2 through the early 1980s (One was titled “Moving Toward Life in a Nuclear Armed Crowd”). It was from him that I learned that the original logic of deterrence, Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) was being replaced as early as the late 1970s with something known as Flexible Response. That evolution continues to this day, with additional nuclear armed actors now factored into the equation.

I had already met some strategic analysts and active and retired military officers during my MA studies at a different university, something that had introduced me to the concept of MAD and piqued my interest enough to want to study under the famous nuclear strategist. Over the ensuing years after I graduated and before I immigrated to NZ I encountered several Air Force missile officers and Navy submariners who at various stages in their careers were responsible for deploying nuclear weapons in operational environments with the real possibility of their being ordered to launch. Without exception these were very sober people, and although they would not share secrets with me they confirmed in casual conversations that US nuclear strategy had come a long way since they days of dumb bombs and MAD.

One things that has remained constant, however, is the deterrent nature of nuclear weapons. The bottom line is that nuclear weapons, although offensive rather than defensive in nature due to their characteristics, are never to be used in anger. They are a form of protective shield for the States that have them, and designed to ward off attacks by more powerful actors or actors that may be inclined to launch nuclear strikes in opportunistic or otherwise irrational fashion. There is an old saying (often attributed to my former professor) in the nuclear strategic community that a maniac with one nuke puts everyone else in check. That is not exactly true for a variety of reasons, but having even a small but demonstrable nuclear force greatly complicates the strategic calculations and physical costs of would-be aggressors. Think of it this way: what if Saddam Hussein did in fact have nuclear weapons and could have delivered them on top of the Soviet SCUD replicas in his arsenal to other regional capitals? What if Gaddafi had that capability? How about the DPRK today or Iran down the road? Would anyone attack them knowing that they could and would retaliate with nukes but without being certain that an attack would fully eliminate their nuclear weapons before use? Who and under what circumstances would take that risk?

Then there is the NonProliferation Treaty (NPT). Entered into force in 1970 it recognized five nuclear states–the US, UK. Soviet Union (now Russia) China and France. They are included in the NPT in spite of their weapons status, so the intention of the NPT was to cement that status quo and direct non-proliferation efforts at other aspiring nuclear powers. Responsibility for controlling nuclear arsenals in the five nuclear states was left to their respective governments. The latter produced the strategic arms limitations (SALT 1 and 2 and START 1 and 2) treaties and intermediate range ballistic missile (INF) agreements between the US and the USSR/Russian Federation. Less significant arms control agreements have been signed, but no other multilateral nuclear arms limitation agreements have entered into force and over the years four countries have violated the NPT and developed their own nuclear arsenals: India, Israel, North Korea and Pakistan. Iran may be on the cusp of doing so and from time to time threatens to do exactly that. To their credit, Argentina and Brazil began to develop their respective nuclear weapons programs but abandoned them by mutual consent in the 1980s. South Africa is reported to have detonated a nuclear device in the 1980s but never went on to developing a full-fledged weapons program.

When I arrived in NZ in 1997 I was surprised to learn that many Kiwis still believed that MAD remainedl the operative logic behind nuclear deterrence. In some quarters it remains a common belief even to this day. Rather than revisit the history of nuclear deterrence and strategy, I thought it would be worth while to break it down into component parts in order to get to the state of play in the current age.

First, a glossary:

ICBM: Intercontinental Ballistic Missile. With ranges over 5,500 kilometres (currently reaching 15,000 kilometres), these missiles are the most powerful weapons ever developed. They are multi-stage boosters that use solid fuels that eliminate the need for rapid fuelling required by boosters that use liquid propellants and are launched into low altitude space orbits before re-entering the earth’s atmosphere and engaging targets. They are the subject of the START Treaties between the US and Russia.

IRBM: Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile. Boosters that have a maximum range of 5,500 kilometres. They are single stage, high altitude liquid or solid fuel propelled and may be armed with conventional as well as nuclear warheads. They are the subject of the INF Treaty between the US and Russia, but dozens of countries now deploy them with conventional warheads.

SLBM: Sea launched ballistic missile. These are boosters launched from surface or sub-surface maritime platforms. They can be ICBM or IRBM in nature and be propelled by solid or liquid fuels (note that liquid fuels are more unstable than solid fuels and hence riskier to deploy). Many SLMBs are conventionally armed but the ones under closest scrutiny are nuclear tipped. SLBMS may be used in “depressed trajectory” targeting where warhead throw-weight (see below) is traded off for the increased speed of a lower altitude path, thereby reducing the time between launch and impact. A scenario for such is a submarine penetrating close to hostile territory (say, a Russian submarine moving undetected close to the US East Coast) in order to reduce the warning time between the firing of an SLBM and the impact on designated strike targets.

Russian Borei-A-class nuclear-powered ballistic-missile sub Knyaz Vladimir at the naval base in Gadzhiyevo, July 3, 2020. Photo: TASS/Getty Images.

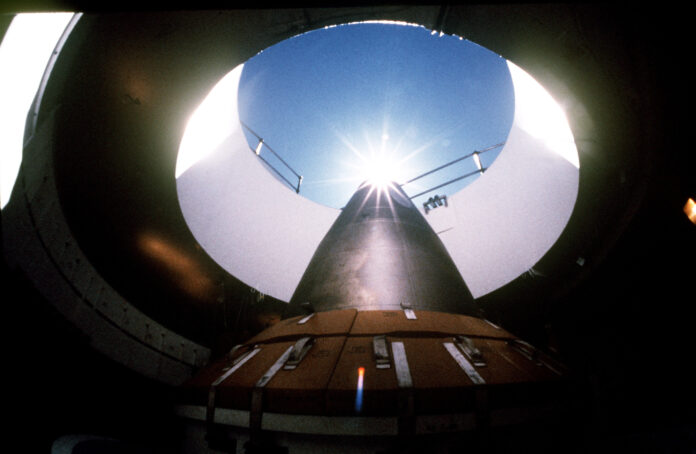

TRIAD: The three legs of a nuclear force, comprised of air, sea and land-based launchers. The concept underpinning the triad is akin to putting eggs into different baskets, in this case in order to promote force dispersion, redundancy and second strike capabilities (see below). ICBMs (land) and SLBMs (sea) have longer reach; air-launched platforms have more flexibility in delivery and targeting options but are more vulnerable (this may change once space-based weapons systems are fully operationalised). The core idea is that a triad makes it difficult for an opponent to “kill” all of a nation’s nuclear forces, especially submarine-based boosters and those located in missile silos buried in thick concrete underground silos or deployed in other “hardened” facilities in remote locations. This allows a State to weather an attack, survive, and respond in devastating kind. That logic is at the core of MAD, but in the contemporary era there is a twist to it.

Throw-weight: The amount (weight) of fissile material a given warhead, also measured in kilotons or megatons of equivalent high explosive. The “Fat Man” plutonium (P-239) bomb that destroyed Nagasaki had a fissile core of 6 kilograms enriched P-239 and a throw weight equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT. The “Little Boy” enriched uranium bomb that destroyed Hiroshima contained 64 kilos of U-235 with a throw weight of 15 kilotons equivalent TNT. “Fat Man” was ten times more efficient that “Little Boy” in its weight to yield ratio, so became the core of the US nuclear arsenal for a decade after WW2.

MIRV: Multiple Independent Re-entry Vehicles. These are the warheads placed in the nose cone of an ICBM or SLBM. They can vary from 3-15 depending on the range of the booster and the throw-weights of the warheads. When the nose cone separates from the final stage of the booster, each warhead tracks to a different pre-programmed target or, if redundancy is deemed necessary (say, against a “hardened” command and control facility), tracks to a target “cluster” that can be hit more than once.

MARV: Manoeuvrable re-entry vehicles. Same principle as with MIRVs, but the warheads are guided in real time by human operators and can switch targets while in flight.

Circular Error Probable (CEP): The circular radius around a target in which a warhead is likely to hit. Original CEP calculations were premised on the probability that 50 percent of munitions fired at a target would land within a certain radius from the target centre. In the contemporary era the estimates are for one warhead aimed at one fixed target rather than the fifty percent threshold. In the Nagasaki bombing the “Fat Man” bomb exploded at 508 meters above a tennis court located 3 kilometres away from its designated target (an airfield). It killed 140,000 people instantly. In the 1970s a Russian ICBM with a payload throw weight of 18-25 megatons (MT) was believed to have a CEP of +/-1 mile after a flight of 10-15,000 kilometres. Today, with various precision-guidance systems, the CEP for a US ICBM carrying <1 MT over 12000 kilometres is less than ten meters (most US nuclear weapons are less than 1 megaton in explosive strength). For cruise missiles and MARVs, CEPs are close to zero. In practice this means that throw weights can be reduced as accuracy increases. Estimates are that a throw weight can be reduced by a factor of four if CEP margins are halved. Along with advances in computer modelling, that is the main reason why the sort of large megatonnage weapons and huge thermonuclear explosions that characterised nuclear testing in the Pacific in the 1950s-1980s are no longer seen today.

Counter-value strike: These involve nuclear strikes against population-heavy targets like cities and large urban centres. They use mid to low altitude air bursts in order to maximize blast damage on soft (non-hardened) objects and structures and help radioactive dispersal via air currents, thereby increasing human lethality. Their military value may be negligible but the physical and psychological impact of high value strikes is devastating to the targeted community whether they survive or not. The desired effect is to either annihilate an enemy society or reduce it to a hyper-vulnerable defenseless mass that can be subjugated. Although justified as military targets, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the victims of counter-value strikes.

Counter-force strike: These involve nuclear strikes against military targets, to include opposing nuclear and conventional armed forces and command, control, communications, computing and intelligence (C4I) centres. Ground-level and penetrative (bunker busting) strikes using shaped warheads focus the kinetic effect of nuclear blasts in order to overcome hardened defenses and structures and, as a secondary effect, reduce civilian collateral damage (because hardened many military-security sites are located away from population centres ). As with counter-value strikes, the characteristics of the target determine the throw weights deployed against them. The desired effect is to terminally degrade a States’s military capability and hold populations hostage to subsequent strikes pursuant to negotiating advantageous surrender terms.

First Strike/Pre-emptive strike: Launching a nuclear attack on an opponent without having been attacked first. This may be caused by imminent defeat in a conventional conflict or in an effort to prevent a nuclear strike, but in any case the concept is married to the notion of a

Second Strike/Retaliatory strike: A nuclear response to a nuclear attack. The premise is that the a State, via its deployment of a hardened and stealthy Triad, will be able to survive a first or pre-emptive strike and retaliate against a first strike opponent. Since the first strike opponent will have used most of not all of its nuclear arsenal in order to prevail without retaliation, failure to do so opens it (and the society that it represents) up to a devastating, even existentially threatening response.

Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD): The logic of deterrence underpinning the first 35 years of nuclear strategy and the so-called “balance of terror.” The logic is based on the first strike, second strike sequence outlined above and on the use of counter-value targeting matrixes.

Flexible Response: Premised on counter-force targeting, this is the strategic logic of nuclear deterrence for the large nuclear powers since the late 1970s/early 1980s. It is based on the belief that a full range of nuclear forces, from artillery fired battlefield nukes to strategic weapons, enhances the de-escalatory logic of deterrence through the full spectrum of force because the escalatory potential of first use in battlefield contexts can be limited to the tactical level and therefore avoid unchecked strategic confrontations. Even so, making it easier to introduce nuclear weapons into battlefields or low intensity conflicts can potentially escalate into strategic exchanges, depending on the command and control structures involved, so it places a premium on command and control self-discipline even in the face of conventional defeat or certain death.

Miniaturisation: The reduction in size of objects, in this case of nuclear weapons and their delivery systems. “Nano” military technologies and platforms are already on battlefields, in the skies and out in space. Warheads are getting smaller, delivery systems more stealthy and less detectable, and C4I systems more sophisticated yet simpler to use. This all augers poorly for strategic arms control efforts.

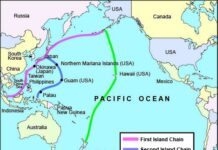

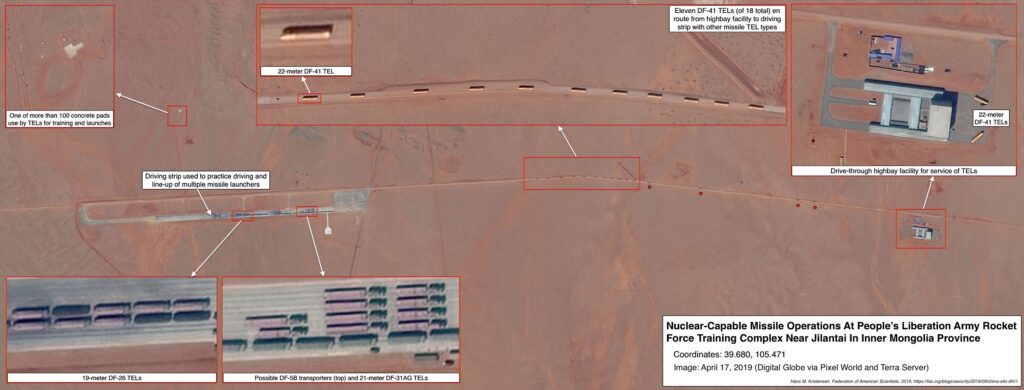

Recent satellite imagery confirms that the PRC is building ICBM missile silo farms in Inner Mongolia and Gansu Province, adding to existing farms in Xinjiang and Qinghai Provinces. This will help strengthen the land based component of its triad because the silo farms’ remote locations are at the limits of US land-based ICBM ranges, will force the US to divert its current ICBMs from other targeting priorities, and are undoubtably hardened. If the silos in each farm are connected by underground transport as well as C4I systems, then the PRC can even play a shell game whereby it moves missiles between silos without having to fill all of them (that assumes that US and other Western sensor systems, be they infrared/thermal or radiation detecting, as well as less sophisticated intelligence gathering methods, are incapable of differentiating between “live” and “cold” silos). The Chinese Navy deploys SLBM carrying submarines and has a host of IRBMs as well, so the combination produced by doubling its land-based ICBMs is yet another measure of its move into Great Power status.

Photo: Federation of American Scientists/Digital Globe (Maxar).

Contrary to much has been written, this may not necessarily be a bad thing if the PRC uses its strengthened land-based missiles as bargaining chips in renewed strategic arms limitation negotiations with the US, Russia and possibly other nuclear powers. Unlike the US, the PRC has a “no first strike” policy regarding its nuclear weapons. Whether one takes them at their word, the Chinese appear to have embraced the deterrent character of nuclear weapons, and given their recent upgrades, may feel more inclined to talk about arms control from a position of strength. In other words, they now have leverage, if not the inclination to use it.

Smaller nuclear states have slightly different logics. France and the UK are heavily reliant on their submarine forces for strategic nuclear deterrence because their land masses are too small for deploying a robust and redundant ICBM fleet. They also tie themselves to the US nuclear umbrella, something that seems increasingly questionable now that Donald Trump has exposed deep flaws in the US political system that undermine its position as a reliable ally. The latter is also true for non-nuclear states like South Korea and Taiwan that have US security and mutual defense guarantees.

Then there are the newer nuclear states. India and Pakistan (which does not have ICBMs at this point) are basically fixated on each other when it comes to nuclear targeting. India’s border conflicts with the PRC and Pakistan’s ties to China complicate the picture in the event of war between the two South Asian neighbours, but for the moment the second-strike, counter-value logic of nuclear deterrence appears to apply to them.

Israel and the DPRK are a different kettle of fish. It is an open secret that Israel has nuclear tipped ICBMs/IRBMs and the will to pre-emptively use them on Iran should Iran drive closer to a nuclear weapons capability of its own. In fact, it has a strong incentive to strike Iranian nuclear and other military facilities before the latter acquires its own nuclear weapons. After all, who will retaliate in kind against Israel given the US security guarantee extended to it? The question is whether, should it launch a first strike on Iran arguing that the Iranians were about to attack them (and Israel has a history of pre-emptive strikes against adversaries), that will open the escalatory Pandora’s box. The answer is probably not, although a counter-value first strike against, say, Teheran might prompt an Iranian to respond on its behalf. But if nuclear retaliation on behalf of the Iranians is not an option, who might come to Iran’s aid and by what means? Would China and Russia risk nuclear escalation by retaliating with conventional force against Israel, thereby bringing the US into the fray? What if Iran responds unexpectedly but not entirely surprisingly by attacking the Saudis, Emiratis or Jordanians (or US regional installations) rather than try to get back at Israel itself? Where will that end?

Iran has indicated that it considers acquisition of nuclear weapons to be a move towards deterrence via a second strike option. But with hardliners calling for Israel’s extermination and the Revolutionary Guard controlling its nuclear program, there may be those in its command and control structure who think that, given the considerable difference in size of their respective land masses, that a counter-value first strike that cripples Israel is feasible, especially if the US proves to be a fickle nuclear ally (or just a paper tiger). Given its constant skirting of prohibitions governing production of weapons grade fissile material and active IRBM and ICBM development programs, trust in Iran to “do the right thing” should it acquire an operational weapons capability is minimal at best and in the case of Israel, non-existent.

North Korean Hwasong-16 ICBM. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

As for the DPRK, it is very difficult to ascertain what their strategic logic is because regime preservation and saving face (as opposed to societal survival) appear to be compelling factors in their calculus. It is unclear if Kim Jung-un and his military commanders accept the “no first strike” premise or if they have the ability to shift from a MAD to a flexible response posture given their strategic disadvantage vis a vis the US. Moreover, they have the PRC on their side, so may believe that they have a degree of impunity should they launch a pre-emptive nuclear first strike on the US, South Korea or a regional target. What is clear is that, given the DPRK’s nuclear arsenal, such an attack would be likely counter-value in nature. The question is against who and what consequences would it bring? Would a strike on Seoul necessarily bring US nuclear retaliation in the face of PRC warnings against it and threats of escalation? Would saving face or the need for a diversion in the face of an uncontrolled pandemic coupled with famine make the Kim dynasty feel compelled to go out in a blaze of (self-perceived) glory? Here the strategic logic of deterrence employed by the Great Powers may not necessarily apply.

Therein lies the rub. The second-strike, counter-value premises of original nuclear deterrence strategies may no longer apply in every instance. First strike considerations, which have always been (the unspoken) part of the strategic logics employed by the Great Powers, may increasingly seem plausible, especially if weapons are miniaturised and attribution of attacks can be plausibly denied and disguised (e.g. via the use of non-state irregular proxies or surrogates). Moreover, autonomous non-state actors with access to (black market) nuclear materials and delivery technologies (even if of the “dirty bomb” type) and without territories to defend have no reason to fear the “return to sender” problem posed by a non-crippling first strike against a nuclear armed opponent. In light of this, the moment has arrived where consideration must be made to not only “broadening the tent” covering those included in strategic and other arms talks, but broadening the scope of the (event if dual use) technologies employed by them.

Turning back to the NPT. It entered into force in another era when less sophisticated weapons technologies were in play and where miniatuarisation was a concept only known to hairdressers (look it up). It has been violated repeatedly, continues to be so and a new nuclear status quo has developed as a result. As the first non-nuclear state New Zealand was a champion of the NPT until the trade obsession the late 1990s and 2000s displaced non-proliferation as a foreign policy priority. Now, with its non-proliferation experts purged and retired from the diplomatic ranks, NZ has only its historical reputation to stand on when addressing the new dangers of a world without effective strategic arms control.

But that could be a starting point for the reform, renewal and revitalisation of the NPT as a multilateral approach to controlling the inexorable technological advances of strategic weapons systems (and perhaps more). Because of its pandemic response and its reaction to the terrorist attacks of 2019, NZ may have a window of opportunity in which to parlay its enhanced international stature into a megaphone for multilateralist bridge-building and peace-making. Given Covid’s global dislocating effects and the failures of international governance systems and practices, to say nothing of the decline of democracy world-wide, perhaps a NZ-inspired move to promote multilateral consensus on curbing some of the less savoury aspects of human endeavour might just be the tonic needed to make the world a safer place.

From darkness, perhaps a light will come.

For a discussion of these themes, please have a listen to the latest “A View from Afar” podcast.