The terms “political risk” and “sustainable enterprise” are not often associated. They should be. The degree of sustainability of an enterprise has direct and long- term cultural, economic, social and political ramifications for the communities in which it is located. The less sustainable the business, the higher the political risk. Conversely, the more sustainable the business the lower the degree of political risk associated with it. The calculation for businesses thinking about whether to go one way or the other is one of long term versus immediate gain: whether to maximize short term profit by focusing on immediate gains while ignoring broader non-economic externalities, thereby incurring higher political risk in pursuit of short-term profit, or reduce political risk by pursuing longer-term gains at a restrained and sustainable rate of profit that factors in non-economic externalities.

The reason that political risk increases with unsustainable business practices is because commerce does not occur in a vacuum. If a business violates workers’ civil or labour rights, if it degrades the environment by polluting the air, ground, and/or water, if it dumps rubbish illegally, causes noise, visual or olfactory pollution, allows unsafe working conditions, bribes local politicians or community leaders, fails to pay a fair share of taxes, ignores cultural mores and conventions, then it runs the risk of alienating the people on which it depends for its success. Those people are not elites who may offer short-term benefits for business. They are the community at large in which a firm operates, and that goes well beyond local luminaries and short time horizons.

Cutting corners and playing loose with rules may help maximize short term gains but set the stage for long-term community resentment and failure. Investors may see short-term unsustainable business opportunity as a means of getting in and out of an economic sector while profitability is at its peak, but that leaves subsequent investors, managers and employees holding the bag when it comes to diminishing returns in a climate of hostility towards the business. Such “cowboy capitalism” is therefore not only unsustainable but also counter-productive to longer-term viability of firms and economic sectors.

There is an even more important reason why sustainable enterprise is preferable in terms of political risk: it promotes and reinforces democracy. Democracy, in turn, provides a safer long-term investment climate because it offers a level playing field and universal rules for competitors that are enforced by a politically neutral state bureaucracy and judicial apparatus, unlike the arbitrary and often capricious nature of authoritarian rule.

As a political system democracy rests on self-restraint and compromise by political actors who are held accountable by the electorate and are subject to the rule of law and transparency in decision-making. Rather than a winner-take all system such as dictatorships, democracies seek mutual second best outcomes whereby political actors, knowing that the pursuit of preferred outcomes by everyone leads to conflict, moderate their objectives in search of compromise. This extends to elections, where parties aim to capture the political center by broadening their campaign appeal, losers agree to abide by the results because institutional guarantees are in place that allow them to compete again at regular intervals, and winners agree to subject their rule to voter scrutiny at those times.

Democracy also involves an implicit compromise between workers and business. Workers agree to contribute to business success by being productive in exchange for business treating them fairly in terms of wages and working conditions. The material terms of the exchange are hashed out via collective bargaining in which agents from both sides, acting as equals, seek to emulate the strategic approaches seen in the political sphere. The more this exchange is reproduced throughout the economy, the more stable is the economic system. The more this exchange is reproduced beyond the shop floor and extended into the social division of labour, the more sustainable the investment climate. The combination of economic stability and social sustainability rests at the substantive core of democracy as not only a form of governance, but as a type of community as well.

Source: Tourism Fiji.

Sustainable enterprise is to capitalism what democracy is to politics: both rely on self-limitation, mutual understanding, compromise, long-term orientation and pursuit of the common good as well as self-interest. Exceptions to the rule and the tidal nature of contemporary democratic politics notwithstanding, the maturity of democracy as a form of social organization rests on these foundations.

That is its most important virtue. Sustainable enterprise has the effect of improving the social and economic foundations of democracy in which the bottom line is measured as much in quality of life and the contentment of the community as it is in material gain.

Trouble in paradise.

The situation in the South Pacific is disappointing on both counts. In the last decade, in spite of myriad attempts to promote good governance and sustainable enterprise, the South Pacific has seen the retrenchment of authoritarian politics and the expansion of non-sustainable approaches to commercial opportunity. Throughout the region unsustainable enterprise has been closely linked with corruption, environmental degradation, human exploitation and undemocratic governance. The fishing, forestry, mining and petroleum and gas industries have been most closely associated with these unsavoury traits as well as the use, in some instances, of private militias and/or corrupt local security forces implicated in the assault and murder of activists, unionists and others.

Nickel mine, Santa Isabel Island, Solomon Islands.

They are not alone. Even industries such as tourism have been accused of engaging in corrupt practices in order to circumvent environmental or basic health and safety regulations. The combination of poorly educated populations, self-serving and unaccountable governments (some dominated by “nobility”) and foreign investors unconcerned about or even opposed to business and government transparency and long-term socio-economic and cultural impact are the key ingredients in the witches brew that facilitates continuation of unsustainable business practices throughout the region.

This is of concern because, taken in aggregate it appears that there is a direct link between unsustainable enterprise, corruption and undemocratic governance in the South Pacific. Although this may favour those involved in the short term, the long term legacies of these practices, as has been mentioned, are deleterious on governance, equitable economic progress and quality of life. All of this takes place against a backdrop of accelerated climate change that has the very real potential for creating the first climate refugees coming from inundated Micronesian island states. In fact, given the limited land masses of even the largest Pacific island states, the adverse consequences of unsustainable commerce and undemocratic governance could precipitate environmental-related political instability sooner rather than later. The time horizons for a change towards sustainability are therefore limited.

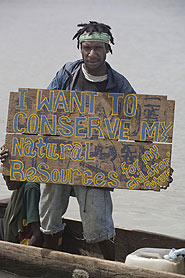

Papuan campaigner against deforestation, 2008. Source: Greenpeace

This does not mean that there are no glimmers of hope for a reversal of this toxic combination. A variety of agencies, including international, non-governmental and civil society organisations, as well as some foreign governments and private business, have endeavoured to promote sustainable development and good governance practices. The problem resides in that most of the agencies are focused parochially on one or the other rather than on the linkage between sustainability and governance. It is there, as a matter of issue linkage between sustainable enterprise, development and democracy, where the most effort and resources need to be directed.

36th Parallel Assessments stands ready to assist current and potential stakeholders in addressing issues of sustainability and governance in the South Pacific and beyond. Through its research and facilitation services it can offer insight into and potential paths towards the promotion of both.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in sustainnews.co.nz, March 3, 2016.