Country Overview (January 2012): Fiji.

Futures Forecast – By Dr Paul G. Buchanan.

The next six months will seecontinued tensions between the Bainimarama regime and its neighbours, Western powers and with the Fijian opposition abroad and at home. Uncertainty will grow around the issue of constitutional reform and election timetabling. There will be no significant signs of improvement in the economy, although the FY 2012 budget contains subsidies and incentives for lower income sectors of the population. The prospects for political unrest remain low.Extending the forecast timeframe to 18 months raises the possibility of deteriorating political and economic conditions due to regime intransigence on the constitional reform and election timetables, against the backdrop of negligible aggregate growth. This could cause divisions within the military hierarchy and prompt public displays of discontent, the latter depending on the degree of organisation extant within the opposition. Uncertainties about business regulations, taxation and operating standards will continue. This time frame is one of fluid and increased uncertainty.

The next six months will seecontinued tensions between the Bainimarama regime and its neighbours, Western powers and with the Fijian opposition abroad and at home. Uncertainty will grow around the issue of constitutional reform and election timetabling. There will be no significant signs of improvement in the economy, although the FY 2012 budget contains subsidies and incentives for lower income sectors of the population. The prospects for political unrest remain low.Extending the forecast timeframe to 18 months raises the possibility of deteriorating political and economic conditions due to regime intransigence on the constitional reform and election timetables, against the backdrop of negligible aggregate growth. This could cause divisions within the military hierarchy and prompt public displays of discontent, the latter depending on the degree of organisation extant within the opposition. Uncertainties about business regulations, taxation and operating standards will continue. This time frame is one of fluid and increased uncertainty.Stability Score.

National Characteristics

Fiji has traditionally been the largest economy in the South Pacific (New Zealand excluded) and the capital, Suva, is the major commercial hub and hosts its largest university (the University of the South Pacific).

Fiji has a population at the last census of 860, 623 (2010). It forms part of Melanesia, and 58 percent of the population are Melanesian. 37 percent of the population are ethnic Indian (descendants of colonial labour imported in the 19th and 20th centuries), and five percent are Europeans, Chinese, and other Pacifika nationalities. Fiji has an official literacy rate of 93 percent but, according to the UN, forty percent of the population live in poverty. It has a GDP of approximately 3 billion US dollars and a 2010 GDP per capita of US$3,610.00 (down from $4,264 in 2008). This is considered by the World Bank to be lower middle income status.

Fiji’s traditional resource base is rooted in agriculture (sugar, most importantly, as it suports 25 percent of the population), forestry, mining (gold, most recently), garment making and fisheries. In the last twenty years tourism has become the major income earner, with 27 percent of GDP generated by the industry (estimated to rise to 40 percent of GDP by 2021). All of the major export industries have declined save gold mining, fisheries and mineral water exportation. In 2010 the sugar industry was nationalised; the bulk of other sectors remain in private hands or private-public partnerships. Fiji manifests sociologically a “dual society” marked by a significant rural-urban and ethnic divide.

The majority of the population and most Fijian Indians live in urban centres on the two main islands, where skilled labour, public services, private business and income levels give modern features to society. A significant minority, mostly ethnic Fijians, live in rural areas in the interior of the archipelago where education, skill, income and social support levels are lower. Here traditional ways overlap with elements of a capitalist socio-economic structure. Because there are pre-modern features to large parts of island countrysides, this gives rise to a “dual” (modern/pre-modern) national society. These divisions have been politicised.

The last ten years have seen a series of crisis resulting in two armed overthrows of the constitutional government, a slowing of economic growth to negligible or negative figures, an increase in net emigration, especially amongst ethnic Indians and skilled labor (repeating an exodus the first occurred after the 1987 military coup), an increase in public debt and a diplomatic and trade re-orientation towards Asia.

Even so, a recent Lowry Institute poll shows that most Fijians, regardless of ethnicity, have confidence in their government and in their economic prospects. Although the methodology of the Lowry polls is in dispute, if true its results demonstrates a dimension of stability to what otherwise could be a volitile context.

Political Environment.

After independence from Britain the 1970 Constitution organised the Fijian political system as a Westminister style parliamentary democracy with a nominated upper house (Senate) and an elected lower house (House of Representatives). After the military intervention of 1987 Fiji became a Republic, replacing the Govenor-General with a President and dropping the designator “Royal” from official titles (although Fiji remains a member of the Commonwealth). Amended in 1997, the constitution was suspended after the coup d etat of 5 December 2006 that imposed a state of emergency and installed Commodore Josaia Voreqe “Frank” Bainimarama as interim, then caretaker prime minister. Constitutional Consultations on rewriting the charter are scheduled to begin in September 2012, and elections have been promised for September 2014.

Post-colonial political conflicts over resource control and land tenure have merged with cultural differences rooted in the dual society syndrome to create a polarised political context. This is a mass praetorian society, where zero-sum approaches to politics result in an “impossible game” of mutually esclusive claims, leading to ongoing stalemate.

In addition to parliament, the Great Council of Chiefs (GCC) serves as a power-brokering vehicle for the ethnic Fijian community. After independence it acted as an advisory body to the government and controled 14 of 32 seats in the Senate (each seat coming from one of the 14 departments that the Great Council of Chiefs are selected from). Prior to the 2006 coup it also constituted an electoral college for selecting the President ad Vice President (formally the Head of State but in practice a largely ceremonial role that defers to the authority of the Prime Minister). Political influence of the Great Council of Chiefs was one motivating factor in the 2006 coup, as the military command opposes ethnic preferences in the distribution of political power and land ownership. After the coup the Great Council of Chiefs was legally restricted in its scope of authority and provincial governors appointed by the GCC were replaced by military officers. After the announcement of the constitutional consultation process slated to begin in July 2012 the regime outlawed and disbanded the GCC, arguing that it was a colonial relic. It is believed the ban is designed to prevent the GCC from having input into the constitutional consultations, and specifically designed to prevent it from asserting its authority or continued presence in any future constitutional reform.

The Methodist Church is a powerful political actor in ethnic Fiji, but has been placed under strict restrictions regarding political activity by the military regime. The traditional week-long Church annual conferences have now been reduced to a day and legal as well as de facto restrictions have been placed on Church social activities that are considered to have political implications.

The labour union movement has traditionally been a signifciant actor in its own right as well as being a balwark of the Fijian Labour Party. Dominated by Fijian-Indians, both organisations have been heavily constrained in their activities by the Bainimarama regime’s security decree legislation.

Regime Characteristics

Commodore Bainimarama leads a soft military-bureaucratic authoritarian regime. The military high command governs as a collective entity with the help of the civilian bureacracy. Its repression is non-lethal and selective rather than murderous and wide-spread.

It operates within a “praetorian” civil-military relations framework where it serves as ultimate guardian of politics, first as an arbitrator between political factions and most recently as a ruler. Besides some personalist aspects of the regime (particularly Bainimarama’s governing stye and the ideological and personal influence of Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum) its greatest weakness is that it is not fully institutionalized, serving instead, by its own definition, as an interim between episodes of elected government.

Chronologically finite in its rule because of the September 2014 election date, its self-defined role is to serve as framer of a new political system and overseer of a new multiracial, egalitarian and democratic society.

Until then, military officers occupy key administrative positions (to include Ministers of Defense, Fisheries, immigration, Police, Prisons, Justice and Postal Services) as well as department governorships.,the Judiciary and Treasury. Significant restrictions on rights of expression and assembly are selectively enforced on regime critics and dissenters (labor unions and political parties have been banned and Parliament dissolved). The 1997 Constitution has been suspended indefinitely pending ratification of a new one, which means that the country is governed by emergency law (recent easing of restrictions notwithstanding). This includes serious restrictions on associational life and media freedom, particularly party and union activities (now regulated by the Essential Industries Bill under which strikes are outlawed) and the coverage of independent press outlets. Foreign observers are pointed to the lack of independence of the judiciary, where local prosecutors an judges have been replaced by Sri Lankan lawyers hired on temporary contracts, and where dissident jurists have been sued or detained for their opinions.

Commodore Bainimarama has already said that he will stand for Prime Minister in 2014. This presumably means that he will retire from active service and lead a military-backed political party in the elections.

As of late 2011 neither milestone has been formalized. This has led to speculation that the Commodore will eventually cancel the 2014 elections and continue to rule by decree (a practice that has seen him engage in significant legislative tinkering in the last two years). For him to do so will require military and majority public support while the Opposition and international community prove ineffectual at preventing his continuation via protests, legal challenges and sanctions.

Another option is to institutionalize military rule. If so, the military will need to support the cancellation of elections and merge more deeply with the civilian bureaucracy while at the same time demonstrating ongoing commitment to the supression of dissent and civil liberties. The merger of civilian and miitary roles in the public service is already happening.

Besides the infusion of military officers into senior ranks of the civilian bureaucracy, retired and reserve soldiers as well as military family members have been shoulder-tapped into the public service, especially in security agencies such as Customs and the Police. The practice represents a colonization of the state apparatus by the military, and is done as a reward for loyalty as well as a way of buying social peace.

The depth of the merger determines the degree to which the state as a whole is militarised, at least in terms of policy orientation.

The more pervasive the colonization, the better the regime is able to exercise control over civil society, although that depends on ideological unity in the miltary cadres working in public service (an open question in Fiji).

At the moment military colonisation of the Fijian state appears to be more a case of patronage than a committed move to institutionalize the military regime.

“Deepening” of military involvement in government can lead to a deterioration of operational skills and readiness as well as political factionalisation within the ranks. There is evidence of that in Fiji. Tensions have risen between Bainimarama and Attorney General Sayed Khaiyum on the one hand, and the Military Council on the other. The latter saw their original blueprint for a return to democracy by 2010 overruled by Bainimarama in 2009, and the framework for the 2014 elections has had no input from it. Several members of the council that supported the coup have departed, including the Defense and Land ministers . In parallel, operational deployment aborad have been curtailed as a result of international sanctions, limiting the promotion prospects for junior officers and soldiers. Given the lack of Military Council input into the eventual transition scenario, it remains to be seen if prolongation of military rule is viable in the face of internal and external opposition to it. Given operational concerns within the ranks, that may be very difficult to achieve.

Succession mechanism

At present (2011) there is no succession mechanism in place for the transfer of political authority in any of the likely transition scenarios (return to civilian rule, continuation of rule by decree or institutionalisation of the military bureaucratic regime). The government has called for a Constitutional consultation to begin in September 2012 with an eye to delivering a new constitution for ratification in September 2013, followed by the time-tabling of elections scheduled for September 2014. F$450,000 has been allocated in the 2012 budget for the establishment of a constitution office and consultation with key stakeholders, including political parties, NGOs and the general public. Subjects of discussion are to include the bi-cameral system, the size of parliament, office term limits and institutional checks and balances. If the convention and ratification process go ahead as promised, the rules and regulations governing elections in 2014 will be established at that time. However no definitive schedule or agenda for the Constitutional Consultations has been announced nor have potential stakeholders been invited to participate, so there is uncertainty as to whether the convention will occur as anticipated. Should it be delayed, it is likely that the 2014 elections will, at a minimum, be delayed as well.

Opposition.

Opposition to the military regime is led by ethnic Fijian leaders grouped in the GCC, the Methodist Church hierarchy, labour unions, student and youth groups and the Fijian Labour Party, plus disaffected former members of the armed forces (including original members of the coup-making clique). There is a vigorous blogging opposition both inside and outside the country. As a whole the political opposition remain divided and disorganised, with domestic opponents subjected to the military regime’s legal constraints, arrest and physical repression. This has hindered organisation of a unfied coalition with eyes on the constitutional convention and elections. At present the opposition is in a reactive mode, waiting to see what the regime does with regards to the constitution-drafting process.

International Relations

Foreign Policy.

Fiji is a fully engaged actor in the global inter-state system.

Fiji’s reputation in the international community was diminshed by the 2006 coup. Although popular at home, it was widely (although not universally) condemned in the international community. Among other reactions, the coup prompted suspension of aid from traditional donors as well as the EU and Asian Development Bank. In order to counter-balance the decline in traditional sources of aid and investment, Fiji has sought out “non-colonial” trade and diplomatic partners under the guise of the “Looking North” policy. This is carried out by a small diplomatic corps of varying degrees of professionalism. One example of the paradigm shift—which along with its shift in military-strategic posture is said to be a “re-balancing” of Fijian foreign relations—is its joining the Non-Aligned Movement in 2010. The move from a Western-centric foreign policy has been welcomed by Fiji’s new partners, with levels of investment from and diplomatic and military ties increasing with China in particular.

Looking North Policy.

The Looking North policy pre-dates the 2006 coup and traditionally referred to Fiji’s diplomatic orientation towards Northern partners, including its colonial master and the United Nations Secretariat.

The process of shifting Fiji’s diplomatic, trade and military-strategic orientation began in the 1990s and accelerated after the 2006 coup, then again in 2009 (when Bainimarama announced the postponement of elections, which prompted Fiji’s suspension from the Commonwealth and PIF along with halting of development assistance from the EU and other international agencies). Although the US has recently resumed some aid progams and upgraded its diplomatic presence in Suva (in part to off-set the expanded Chinese presence in the region), Australia and New Zealand continue to defer full diplomatic relations with the military regime. The result has been a marked re-orientation in Fijian foreign policy during the last five years.

See also: foreignaffairs.gov.fj

Military.

Force composition

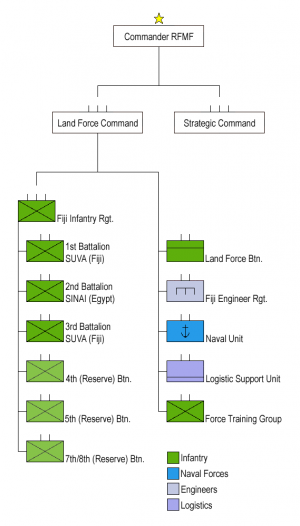

The Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) is comprised of 3500 active duty and 6000 reserve soldiers. A 300 sailor Navy complements six infantry ( three active duty, 3 territorial reserve) and one engineer batallion in the Army. The Navy conducts inshore patrol and search and rescue operations on nine patrol boats, while the 1st and 2nd infrantry batallions traditionally serve under UN Command overseas. There currently is no Air Force. The military is predominantly ethnic Fijian, although Indo-Fijians are found in the officer ranks (the Navy in particular).

Since 2003 many in the Fijian military have left service to join private military companies (PMCs), as have many retired military personnel and reservists (more than 3000 in 2007). Another 2000 serve in foreign militaries, mainly that of the UK. They contribute heavily to the inflow of overseas remittances to the republic, which is significant because remittances constitute the second largest source of foreign exchange earnings (after tourism). Departure overseas of military-qualified personnel also serves as an oulet for discontent or untoward ambition within the ranks as well as an economic boon, so the practice is encouraged.

Deployments

Involvement in UN peace-keeping operations is a source of professional training and advancement so is highly regarded within the armed services.

Political role

With roots in traditional warrior culture, the Fijian military has a long history of political intervention, having staged coups in 1987, 2002 and 2006. The politisation of the military was assurred by corruption and incompetence in civlian governments.The military swears its allegience to the nation, not the Constitution (as was seen by its suspension of the 1997 Constitution in 2006 and stated intention to re-draft a new one). It considers itself above politics and the guardian of the people, and as such defines the national interest on its own terms.

Government Statement:

The current military worldview is summarised by Commodore Bainimarama:

Ref. rfmf.mil.fj/news/Commanders%20Intent.html

“If you don’t like change, you’re going to like irrelevance even less”. General Eric Shinseki

- INTRODUCTION

1.

Our recent history has it, that we have risen to meet and shape our moments of transitions. This is one of those moments. We live in a time of sweeping change. Globalisation has accelerated to an unprecedented level and this has opened doors of opportunity around the globe but also intensified the dangers we face from international terrorism and the spread of deadly technologies, transnational crimes, to economic upheaval and a changing climate.

Our recent history has it, that we have risen to meet and shape our moments of transitions. This is one of those moments. We live in a time of sweeping change. Globalisation has accelerated to an unprecedented level and this has opened doors of opportunity around the globe but also intensified the dangers we face from international terrorism and the spread of deadly technologies, transnational crimes, to economic upheaval and a changing climate.

2. According to Charles Darwin “It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the most responsive to change”. We rose in December 2006 to change the political and governance landscape of our government and nation. This includes changing the culture and attitudes of our people and leaders and more specifically that of our civil servants, politicians and vanua leaders in the way they deliver services to the people. This change agenda is encapsulated in our vision for Fiji “to become a more progressive and a truly democratic nation; a country in which its leaders, at all levels, emphasise national unity, racial harmony and the social and economic advancement of all communities regardless of race or ethnic origin. The overall objective of this vision is to rebuild Fiji into a non-racial, culturally vibrant and united, well-governed, truly democratic nation that seeks progress and prosperity through merit-based equality of opportunity, and peace”.

3. The approach to this broad objective is now defined in the People’s Charter for Change, Peace and Progress. The achievement of this vision I believed will pave the way for a stable and peaceful Fiji. In another view the achievement of my vision ultimately means brings security for all as the lack of unity and all-encompassing policies were the major setbacks prompting instability in our recent history.

4. Furthermore, the Charter is the master doctrine for the nation today and has implications for us all. Being the institution that initiated this change process, I expect every member to have a good understanding of the document and ensure you make relevant contributions where appropriate. For strategic and operational level planners and decision makers, you must discern the change that is meant for us and incorporate that into our strategic and operational plans. We started this change and we must ensure we continue to make the necessary transformation within, in order to sustain our national effort in this process.

5. Reform, Change, Progress and Transformation seems to be the dominant theme of the moment. I believed that this theme is more relevant now to the RFMF than any other time of our history. We took the first step to making the many changes occurring in the governance of our nation today, and we exist to guarantee that those changes come to fruition. Our participation in this change process has exacerbated some gaps in our capabilities. We need to identify these gaps and make the necessary transformation in order to rectify them and sustain our relevance in the various roles and responsibilities required of us.

6. Change in the global strategic environment is immense, moreso in the balance of power in our wider region. This needs proper evaluation and analysis as it impact on our perceptions, opinions and more so on our security and defence structures and systems.

Nature and Scope of our Defence Functions

7. The RFMF is the last bastion of law and order, and defence of the sovereignty of Fiji. The RFMF remains a commited provider to the Government and the Commander RFMF, as advisor on military policy, strategic analysis and operational commitment. Encompassing this is the use of military capabilities in situations of natural disasters, civil unrest and our commitment to peace and security around the globe.

Fiji’s Defence Policy

8. We have not displayed our defence policy explicitly and there have been several attempts to develop one. Neither of the past two Defence White Papers has been implemented. The 1997 White Paper had emphasized external threats in its analysis and advocated a defence posture that would provided for ‘real deterrence (and) real combat capability’ in order to preserve national sovereignty ‘on land and sea’. Thus it had proposed the concept ‘Defending Fiji’ as a basis to defence policy and a force strength ‘of sufficient manifest capability’ to deter ‘aggressor nations’.

9. This White Paper was not implemented despite Parliamentary approval because, according to the Draft White Paper of 2005, it was considered ‘impractical and too costly to implement’. The 2005 Draft White Paper, which was based on the 2004 Defence Review, had called for a reduction in the size of the RFMF, mainly due to what it considered the absence of any external threat to the nation from the armed forces of another country. However, this was also never implemented, in large part due to opposition from the RFMF and the lack of merit in their other recommendations.

10. The basis for defense policy therefore is the RFMF Act. This is usually supplemented by our own Strategic Plan and yearly Commanders Intent. According to our Stategic Plan 2008 – 2012, Fiji’s defence policy provides the framework for future decisions about military capabilities, reserves and funding. Within this framework, the six key defence policy objectives are:

a. Protecting Fiji’s sovereignty, independence and interests;

b. Overall security of the country;

c. Wellbeing of our people

d. Contribution to international peace and security

e. Credible integrated security approach

f. Maintaining strategic alliance; and

g. Providing shipping and navigation services.

Our National Values, Vision and Principles

11. We exist not only to defend our sovereignty and territorial integrity but our values and interests. National interest refers to what is good for the nation as a whole in international affairs and what is good for the nation as a whole in domestic affairs commonly referred to as the public interest. National interest lies at the very heart of the military and diplomatic professions and leads to the formulation of a national strategy and the calculation of the power necessary to support that strategy. The Peoples Charter for Change, Peace and Progress identified our interests as follows:

a. We believe in God as a higher power that is in every human and in all of nature and creation. Therefore, as trustees of our Creator, God, we are all one and inseparable from the source of all creation.

b. As one people, we are one nation, basing our solidarity in love, dignity, humility and humanity, as we all are loved by our Creator.

c. We respect, appreciate and celebrate the diversity and the aspirations of our people.

d. We recognize the freedom of our various communities to follow their beliefs as enshrined in our Constitution.

e. We strive to live justly and peacefully with one another, in the knowledge that good-will alone is not sufficient to sustain peace, just governance, and freedom.

f. We accept that we must live by a set of shared moral values and standards, through which we evaluate our individual and collective conduct and performance.

g. We hold that these values and standards are the basis of the common good which we hereby define as consisting of the following principles and aspirations:• equality and dignity of all citizens;

• respect for the diverse cultural,

• religious and philosophical beliefs;

• unity among people driven by a common purpose and citizenship;

• good and just governance;

• sustainable economic growth;

• social and economic justice;

• equitable access to the benefits of development including access to basic needs and services; and

• merit based equality of opportunities for all.h. We seek to safeguard, preserve and value our environment as we benefit from it.

i. We seek to achieve this through consensus so that our people will have a moral vision that will guide our development and governance and that will give our people the responsibility to sustain the common good.

Fiji’s National Interests

12. The nation’s primary concern are the interests of the people and the State based on values and beliefs assumed and pursued by the various communities by which security, protection, safety and prosperity of her people are ensured through the stable existence and functioning of the state. This includes:

a. Guaranteeing the maintenance of Fiji’s sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence;

b. Development and preservation of democracy, welfare, security and safety of Fiji’s citizens;

c. Maintenance of human security and stability of society;

d. Meeting regional and international commitments.

RFMF Vision

13. We want to be “A smart military force that enhances its capabilities beyond its size through professionalism, resourcefulness, knowledge and skills, leadership, discipline and adherence to its ethos and values”.

Our Mission

14. The RFMF Mission is to enhance the security of the Fiji Islands and protect its people and interest in peace, in crisis and in conflict. RFMF Ethos 15. Our enduring ethos is based on truthfulness, fairness, and transparency interpreted as “Na Dina, Dodonu kei na Savasava”.

Our Values

16. The RFMF is a value based institution that defines acceptable standards which govern the behaviour of individuals within our organisation. These common norms of behaviour support the achievement of our mission and goals. It is important that we constantly communicate our values and confront contradictory behaviour. Our values are:

a. The Will to Win. Defending Fiji and its interests and maintaining order is meaningless unless there is a will to win. In fostering the will to win, the RFMF encourages professionalism, determination, tenacity, physical fitness, self -confidence and controlled aggression.

b. Dedication to Duty. All members of the RFMF must remain committed to their obligations and be physically and mentally capable of performing their tasks at all times. Consequently, the RFMF views seriously any impediment to those capabilities such as misuse of alcohol and ‘yaqona’, the illegal use of drugs and extra-marital affairs. The RFMF expects, when ordered, soldiers will be able to serve without unreasonable constraint, on duty or otherwise, in isolated or remote locations, on temporary or long term detachment, and on call-out or deployment to a contingency or military operation.

c. Integrity. Integrity is the soundness of moral character and principal. Integrity is essential to all service personnel as it implies honesty, sincerity, reliability, unselfishness and consistency of approach. Leaders at All levels are required to uphold and enforce discipline fairly and without bias. Their conduct is to be such that it neither calls into question their integrity, nor brings the RFMF into disrepute. Maintaining integrity ensures the trust and the respect of the soldiers whom commanders are privileged to lead.

d. Teamwork. The bonds of teamwork are equality, trust, tolerance and friendship. It is about understanding and sharing the same vision and contributing together towards achieving the vision. Together as a Team the RFMF can achieve beyond its size.

e. Courage. In training and in operations, there will always be difficulties and hardship. Danger must be met with firmness and with control of personal and group fear. Courage is the physical and moral strength upon which fighting spirit and ultimate success in all facets of RFMF life.

f. Family. The RFMF is a people’s orientated institution. It is therefore vital that we recognise and respect the value and contribution of families to the success of the institution.

17. The above values are ‘combat multipliers’ that are invaluable to the operational capacity of a small military formation like the RFMF. Equally as important in our return to our constitutional role is to regain our professionalism and military cohesion. In order to reinforce this, the RFMF training focus for 2011 is on fostering professionalism, and perfecting basic military skills and discipline.

18. It’s been four years since we tookover the leadership of our nation. The takeover was provoked by the rot in the governance of our nation. The sense of optimism, confidence and a bright future for a united Fiji that was echoed during our independence 40 years was shattered after years of disunity and corruption. We decided in 2006 that compliance of our stipulated role in the defence of Fiji, we assume the helm of the leadership and attempted to transform Fiji into “becoming a more progressive and a truly democratic nation; a country in which its leaders, at all levels, emphasise national unity, racial harmony and the social and economic advancement of all communities regardless of race or ethnic origin. The overall objective of this vision is to rebuild Fiji into a non-racial, culturally vibrant and united, well-governed, truly democratic nation that seeks progress and prosperity through merit-based equality of opportunity, and peace”. Getting this vision achieved is not easy and needs a huge transformation in the attitude, culture, relationship and dynamics of our nation. It also requires a transformation within the RFMF because in our new focus our attitude, culture and capabilities have to be transformed to sustain our commitment to 2014 and beyond.

19. Transformation, Progress, Change and Reform are the basis of our assumptions and are the themes of my Intent for 2011. Every change we make at the national level will have some form of implications and effect in the RFMF. And given our current role of internal security and governance our imagination must be sound and transformed in order to be ahead of our national effort. We are the drivers of the change at the national effort and this must be reflected within.

20. At the international level, our traditional friends have deserted us. They do not want to understand us and only care about imposing their political ideologies and beliefs on us. God has been merciful and kind to us. New friends have come to our aid. We have transformed our Look North Policies, international relations, trade and economic relations, and defence partners. This has some implications for us now and into the future and we must appreciate this development and carry out the necessary transformation within.

21. Our image, reputation and credibility with the UN and MFO needs transformation as well. We need to a huge shift in our thinking, in how we do things with them. They have changed to be appreciated and planned accordingly. This must be incorporated in the review of our Strategic Plan for the next five or so years. Defence people like us must plan 20 years ahead, more so in this age of constant change. PURPOSE 22. This intent is my direction for 2011. It is the main direction for 2011. Because of constant changes in the environment there will be diversions along the way but we will need to review as we go along. But if we are required to redirect efforts elsewhere we must at the completion of those requirements quickly re-orientate and surge ahead. “MAY THE LORD BLESS US ALL”

Republic of Fiji Military Forces © 2010

It is clear from the Commodore’s statement that the project of national revitalisation that he envisions unde the People’s Charter for Change, Peace and Progress is a long term process that will require major transformation of Fiji’s institutional culture, social mores, economic machinery, political organisation and strategic outlook. As such, it is at odds with the timetable for a return to civilian government and elections in 2014. That has given rise to concerns that Bainimarama has no intention of giving up power on that date. If that is the case, he will need complete military support as well as that of key civilian actors for the extension of authoritarian rule to be successful. This will also require the longer-term supression of opposition groups, all in the face of continuing international sanctions. That means that the military role is paramount in any transition scenario.

Economic Features.

Fiji continues to rely on the colonial industry, sugar, as a major income earner. The sugar industry has been in decline for over a decade, along with other traditional sources of revenue such as garment making and forestry. Although mineral water exports, fisheries and gold mining have increased, the overall rate of growth has remained roughly the same since 2005, hovering between -0.5 to +0.5 percent. Tourism is becoming the largest source of revenue in recent years, with a record numbers 6000,000 visitors in 2010, although heavily discounted travel packages (done in part to off-set negative publicity stemming from the coup) means that the impact of increased tourist trade has not had a significant impact on growth. Development of foreign owned resort complexes in remote locales has increased the presence of “enclave” micro-economies throughout the archipelago.

In terms of percentage of GDP, agriculture occupies 9 percent, manufucturing 24 percent and services 77 percent of total output (2004, with the trend in production accentuating in recent years). This has produced serious dislocations in the traditional economic landscape, which in turn has forced a re-orientation towards value-added production amid political conflicts about future growth and job creation.

The Fijian government promotes Fiji as regional telecommunications hub and is encouraging foreign investment in IT and subsidiary industries (most of the capital invested in Fijian IT start ups is Indian). Chinese investment in the sector has increased with an eye to making Fiji a telecommunications hub for the South Pacific (Fiji is a midway transit point for the fiber optic cable connecting Australia and New Zealand with the US via Hawai’I, and thus has privileged access to its data flows). In spite of these and other efforts to attract investment into value-added production, foreign direct investment declined 1.1 percent in 2010 (US$264 million, down 36% from 2006). The Fijian government forecast for 2011 predicts a rise to US$800 million, although this should be considered to be optimistic.

Ref: See, Fiji Government National Investment Policy Statement.

FDI is concentrated in the tourism sector, mineral extraction, telecommunications, manufacturing, services and construction. Australia is the largest source of FDI, followed by several South Asian states and China (which pledged $83 million in soft loans in 2008 and which has signifcantly upgraded its investment in construction, telecommunications and tourism, to include building the new Chinese embassy in Suva). Fiji encourages investment from the Middle East as an off-set to declines in Western investment outside of the tourist sector.

Given economic and political uncertainty, investment prospects are perceived as mixed and limited to a narrow range of productive sectors

See also: http://www.reportbuyer.com/countries/asia_pacific/country_report_fiji_april_2011.html

Following a 20 percent devaluation of the Fijian dollar in 2009 and the negative impact of rising fuel prices and weather on agricultural production, inflation averaged around 8 percent during the last five years.Public Sector wages account for over 50 percent of government expenditures, and the debt to GDP ratio stands at 56 percent. Changes in the tax regime have been mooted, which will have an impact on tourists and foreign investors.

Remittances are the second largest source of foreign income in Fiji, jumping from US$30 million to over $300 million between 2002-2007. They contribute a third of Fiji’s foreign exchange reserves and reach forty percent of the population and ten percent of GDP. Fiji moved from a sustainable to a remmitance state in the early 1990s due to demographic and economic trends that led to labour surpluses in the domestic market (the decline of traditional export industries coupled with a high reproductive rate leading to a rise in youth unemployment), and that trend has continued since in spite of the rise of tourism and non-traditional export industries. 6000 Fijians emmigrate yearly, and although most are permanent expatriates (only 30 percent return), a significant number after 2003 work on short term contracts (mostly associated with PMCs, several of whom have recruiting offices in Suva). Remmitances are mainly used for household consumption and some asset purchases, but also find their way into infrastructure development via community funds. Remmitance destinations are predominantly rural ethnic Fijian, where informal cash economies parallel and at times supercede formal economic institutions and procedures.

Most remitors are unskilled labour migrants to Australia, New Zealand and the US, with an increasingly significant number employed in the Middle East and Central Asia in military or paramilitary roles.Two thirds of annual remittances come from these two groups. Skilled labour migration is mostly Fijian Indian and permanent, with a corresponding decline in monies sent back home.

Foreign Direct Assistance is estimated at US$37.5 million for 2011-2012. $18.5 million comes from Australia. The remainder comes from several South Asian states, China, Japan, New Zealand and International Non-Governmental Organisations. Most recently USAID has resumed operations within the country.

Official estimates show that unemployment hovers at around nine percent of the work age population, although if informal sector and piecemeal labor is included the figure doubles.

Crime and Corruption.

Fiji enjoys relatively low levels of street crime, and serious crime (murders, armed assaults, rapes) are mostly confined to disadvantaged areas in urban centres or are connected to inter-personal disputes.Thefts and robberies involving tourists are infrequent. Generally speaking, night travel is safe for women, and rural areas tend to be safer than urban centres. However, the issue of organised crime is a growing problem, as Asian-based criminal netowrks have used Fiji’s new trade and investment orientation and porous border controls to set up legitimate businesses as fronts for criminal activity, drug and human trafficking and money laundering in particular. The problem is region-wide but Fiji’s strategic position makes it the cog in the wheel.

See also: http://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=10768211

Corruption is a deep-rooted problem in Fiji. Although the military and diplomatic corps show a fair degree of professionalism and honesty in the ranks, the civil service and private market are considered rife with malfeasance. The police, imigration and customs officers, building inspectors and permit-issuers, and some officals involved in larger investment oversight have been implicated in bribery schemes. Conflicts of interest, abuses of authority, fraud, nepotism, miuse of public property and financial mismanagement round out the long-standing picture. The cultural tradition of “koha” (contributions) lends itself to non-transparent exchanges of favour. Although an anti-corruption agency exists, it is heavily politicized, dominated by the military and, except for its targeting of dissenters, largely toothless.

Infusion of Chinese capital has been associated with a rise in corrupt practices in the industries in which it is invested. Because Chinese labour is imported to complete many projects, there is concern that this practice facilitates criminal activity as well as resentment from the local poplation. The presence of organised crime syndicates has raised concerns with INTERPOL and Western security agencies, but the diplomatic stand-off between the coup leadership and Western states has impeded cooperation.

Conclusion.

The economy will remain stagnant over the near term as political uncertainties compound the decline of traditional export industries and their replacement by a mixed service sector (tourism, telecommunications, finance and real estate) backed by Asian capital.

The 18 month forecast is one of medium to growing risk, with a probability of increased risk if the 2009 milestones are missed.

* Note:

-The stability score is an assessment of the political and market risk extant in the country on a score of 1 (high risk) to 10 (low risk).

It is derived by adding a political risk score (on a scale of 1-5) to an economic risk score (1-5) up to a possible total of 10 (very low risk).

The scores are based on the data provided by Transparency International, Freedom House, World Bank, CIA, Asian Development Bank and numerous other sources. It is based on an averaging of country ratings given in these sources. Due to the number of variables and difficulties in coding complex phenomena, scores are not quantitatively rigorous and represent a qualitative assessment based upon open sources of information.

Useful Links:

http://www.foreignaffairs.gov.fj/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=66&Itemid=97

Fiji Defence Logistics (Non Government Entity)

http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/fiji/fiji_brief.html

Asia Development Bank 2011, “Pacific Economic Monitor”, February http://www.adb.org/Documents/Reports/PacMonitor/pem-feb11.pdf

World Bank 2010, “Emerging stronger from the crisis” East Asia and Pacific Economic Update, Volume 1 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEAPHALFYEARLYUPDATE/Resources/550192- 1270538603148/eap_april2010_fullreport.pdf

World Bank 2011, “Country Pages and Key Indicators”, East Asia and Pacific Economic Update, Volume 1 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEAPHALFYEARLYUPDATE/Resources/550192- 1300567391916/EAP_Update_March2011_fiji.pdf

Fiji Island Bureau of Statistics 2009, “2007 Census of Population and Housing”, Statistical News, Number 9, 27 February http://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/Census2007/Release%202%20- %20Labour%20Force.pdf – Accessed 28 March 2011.

Reserve Bank of Fiji 2011, “Economic Review: Month Ended January 2011” Economic Review, Volume 28, Number 1 http://www.reservebank.gov.fj/docs2/Economic%20Review%20January%202011.pdf – Accessed 28 March 2011.

ABC Radio 2010 “Fiji’s economy suffering under military regime” on Pacific Beat, 27 May http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/pacbeat/stories/201005/s2911316.htm

“Concern over increasing unemployment in Fiji” 2010, Fijilive, 7 May http://www.allvoices.com

Narsey, W., 2010 “Fiji‟s Censorship and Deeper Darkness during Diwali” Coup Four and A Half, 12 November http://www.coupfourandahalf.com/2010_11_07_archive.html –

US Department of State 2010, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2009 –Fiji.

Firth, S & Fraenkel, J. 2009, “The Fiji military and ethno-nationalism: Analysing the paradox,” in The 2006 Military Takeover in Fiji: A Coup to End All Coups, eds. J. Fraenkel, S. Firth & B. Lal, Australian National University Press.

Lamour, P. 2010, “Corruption and Legal Pluralism”, Keynote address to Conference on Legal Pluralism Port Vila 30August to 1 September 2010 on the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute website – http://www.paclii.org/law-and-culture/larmour.pdf

Narsey, W., 2010 “Fiji‟s Censorship and Deeper Darkness during Diwali” Coup Four and A Half, 12 November http://www.coupfourandahalf.com/2010_11_07_archive.html

[TO DO: All of the links I sent earlier.]