Weekly Analysis: Chile’s Pacific Presence

Analysis – By Dr Paul G. Buchanan

Most attention focused on the South Pacific is directed at its Western fringe, where the majority of inhabitants reside and where, consequently, the political dynamics are the strongest. But the Southeastern Pacific, while underpopulated and lacking in the land masses of its southwestern neighbors, is nevertheless an area of great strategic importance.This is due to its being a major sea corridor between South America and Australasian markets, and to the fact that it is a major fishery repository that is now under threat. There is also the potential for deep sea resource exploitation along the lines currently being undertaken in the Southwestern Pacific. In a previous weekly assessment 36th Parallel Assessments has covered the French Polynesian territories that occupy the mid South Pacific and which border on Chilean Pacific Island territory. In this week’s analysis we look at these Chilean possessions and its approach to regional geopolitics.

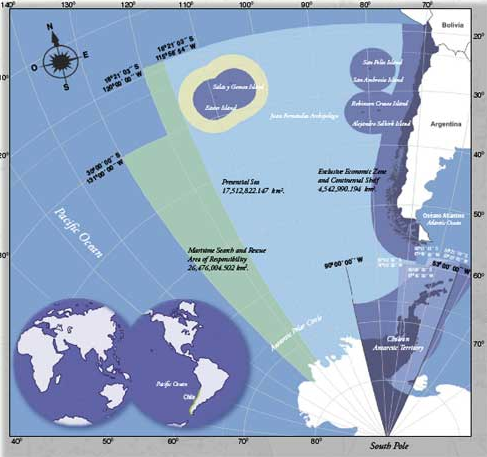

Most attention focused on the South Pacific is directed at its Western fringe, where the majority of inhabitants reside and where, consequently, the political dynamics are the strongest. But the Southeastern Pacific, while underpopulated and lacking in the land masses of its southwestern neighbors, is nevertheless an area of great strategic importance.This is due to its being a major sea corridor between South America and Australasian markets, and to the fact that it is a major fishery repository that is now under threat. There is also the potential for deep sea resource exploitation along the lines currently being undertaken in the Southwestern Pacific. In a previous weekly assessment 36th Parallel Assessments has covered the French Polynesian territories that occupy the mid South Pacific and which border on Chilean Pacific Island territory. In this week’s analysis we look at these Chilean possessions and its approach to regional geopolitics.Chile has 6,435 km (3,999 mi) of coast line, 4,300 of which front the mainland coast and the rest distributed along Chile’s Antarctic and Pacific Island territories. The latter include Easter Island, which is situated more than 3,218 kilometers (2,000 miles) west of the mainland. The most remote possession of any Latin American country whose nearest neighbor, Pitcairn Island, lies 1200 miles to the West, Easter Island is a volcanic land mass with an area of 117 kilometers (45 miles) and a subtropical climate. Chile’s other island possessions are Sala y Gómez island, San Felix and San Ambrosio islands in the Desaventurados (Misadventure) chain, and the Juan Fernandez Islands. Easter Island is a World Heritage area and all of Chile’s island territories are classified as national parks. Chile’s maritime claims include a contiguous zone of 24 nautical miles (nmi) (44.4 km; 27.6 mi), a continental shelf 200–350 nmi (370.4–648.2 km; 230.2–402.8 mi), an exclusive economic zone 200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi), and a territorial sea of 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi). All together, Chile’s maritime territory, including the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf, covers more than 4.5 million square kilometers, with its Area of Responsibility for Search and Rescue (SAR) covering 26.4 million square kilometers.

With a maritime history that dates back to the mid 19th century, Chile has always been dependent on the sea for trade, and as a result has developed robust naval forces to defend both its economic as well as physical integrity. Blooded in a number of 19th century conflicts that included anti-piracy efforts and skirmishes with Argentine and Peruvian forces that culminated in the 1879-1883 War of the Pacific (where Chile defeated Bolivia and Peru in a territorial conflict). The consequences of La Guerra del Pacifico are felt today, particularly in Bolivia’s continued demands for access to the Pacific coastline that it lost in that war. These claims are supported by Peru, which also lost territory in that defeat. That makes the Northern land and maritime border issues a source of ongoing Chilean geopolitical concern.

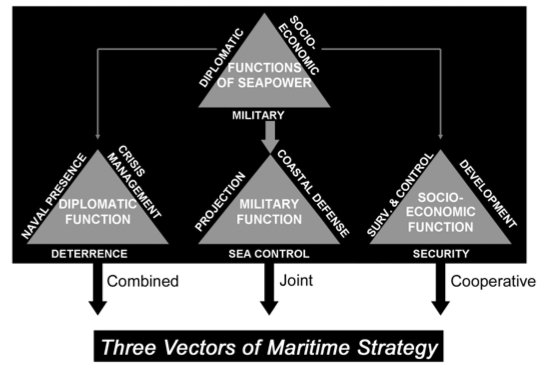

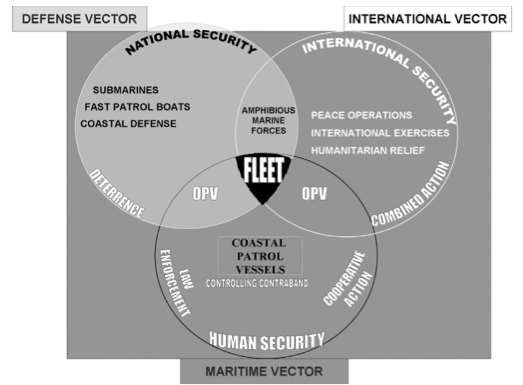

The Chilean navy is considered to be the most advanced in Latin America, rivaling Brasil in regional importance (they share no borders, even if Chile has South Atlantic island possessions abutting the Magellan Strait that intersect with Brazilian Antarctic claims). Modern Chilean maritime strategy, which is based on the three “vectors” of national defense, diplomatic relations and socioeconomic development, is focused on maintaining a high profile presence in the strategic triangle that extends from the northern and southernmost points of the mainland west to Easter Island (since Chile’s Antarctic territory disputed, the strategic triangle does not include it for the purposes of this discussion). This makes Chile’s maritime jurisdiction the largest in the South Pacific, and its presence in the Eastern half of the region is commensurate with that.

36.1 percent of Chilean exports pass through South Pacific high sea lanes on their way to Asia, and nearly 40 percent percent transit the Eastern South Pacific towards the North American West Coast and Central America. Likewise, the vast majority of Chilean imports arrive by sea. China is now the largest export destination for Chilean goods and the second largest source of imports. According to the OECD, exports to Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, India, China and Australia amounted to 3.388 billion US dollars in November 2011 alone, over half the monthly total (with minor variations this monthly trend holds true for all years since 2010). In fact, 88 percent of Chilean commerce, involving 51 percent of the national GDP, flows through the South Pacific (2009 figures). In 2009 43 million tons of goods flowed out of, and 36 million tons of goods flowed into Chilean ports. Chile also maintains commercial air links with French Polynesia, New Zealand and Australia, and is a party to the P-4 (Brunei, New Zealand, Singapore and Chile) free trade agreement as well as the currently being negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement.

Given its lack of strategic depth (the Chilean land mass averages less than 120 kilometers across its 43oo kilometer length), Chilean military strategy has always been premised on a robust defense of its coastal waters. In recent years, buoyed by the commodities boom that has seen the price of Chile’s major export, copper, soar on international markets, the Chilean Navy has undertaken an extensive modernization program focused on acquiring new systems from British, German, Dutch, French, Israeli and US suppliers (it should be noted that by laws passed during the military regime of 1973-1989, 16 percent of pre-tax copper revenues are paid directly into the military budget, which is then distributed via inter-service negotiations. Although the law has been repeatedly challenged during the post-authoritarian era, it remains in effect as a means of re-orienting and maintaining the military gaze away from domestic political issues). The bottom line is that the Chilean Navy is a modern blue water fleet with a high degree of professional competence and technological sophistication in a number of combat and on-combat operational areas that maintains a significant presence in the Eastern South Pacific.

Geography and Demographics

With a resident population of around 5500 (half of which are indigenous Rapa Nui), Easter Island is the most notable of Chile’s island possessions. Its unique cultural artifacts and natural beauty has made it a prime tourist destination, although it also historically represents a glaring example of social decline tied to ecological devastation (the famous Moai head stone sculptures were almost completely toppled in pre-modern conflicts over resources that resulted in the death and exodus of many of its native population prior to the arrival of Europeans). From a high of 15,000, the population at the time of European discovery (1722) was less than 3000, which fell to a low of 111 in the late 1870s before slowly recovering to its present level. After the destruction of the indigenous culture, European settlers attempted to sheep and copra farm without much success. It was not until the advent of tourism in the late 20th century that the island began to exhibit signs of revitalization.

With a resident population of around 5500 (half of which are indigenous Rapa Nui), Easter Island is the most notable of Chile’s island possessions. Its unique cultural artifacts and natural beauty has made it a prime tourist destination, although it also historically represents a glaring example of social decline tied to ecological devastation (the famous Moai head stone sculptures were almost completely toppled in pre-modern conflicts over resources that resulted in the death and exodus of many of its native population prior to the arrival of Europeans). From a high of 15,000, the population at the time of European discovery (1722) was less than 3000, which fell to a low of 111 in the late 1870s before slowly recovering to its present level. After the destruction of the indigenous culture, European settlers attempted to sheep and copra farm without much success. It was not until the advent of tourism in the late 20th century that the island began to exhibit signs of revitalization.

Easter Island currently receives around 80 thousand tourists yearly and has in recent years upgraded accommodation and transportation facilities so as to offer a full range of eco-tourism-related services. Although it has become the primary source of hard currency revenues on the island and a significant tax resource for the Chilean government, tourism on Easter island has also brought with it serious problems with sewage, sanitation, energy consumption and pollution. It is the site of a bitter conflict between the Chilean government and Rapa Nui islanders (Rapa Nui is also the indigenous name for Easter Island), who are of Polynesian lineage and who share cultural and linguistic traits with New Zealand and Cook Island Maori. Although the Rapa Nui enjoy a “special status” under Chilean law, they remain subject to mainland authority, something that has been a source of tension that have episodically spilled over into civil disobedience, public protests and low scale violence on the part of sectors of the indigenous population (the last serious disturbance being an extended land dispute and hotel occupation in 2010-11 that ended with a police armed intervention). There is a pro-independence movement on the island, although its activities have been more rhetorical than practical. The major social tensions at present involve attempts to limit the number of tourist visitors per year (Rapa Nui prefer less than 50,000 but tourism operators want double that), and the continued immigration of mainland Chileans who compete with local labor in the tourism-related workforce (wood carving in particular).

Isla Salas y Gómez is located 3,210 km west of the Chilean mainland, 2,490 km west of the Desaventuradas Islands, and 390 km (236 miles) east-northeast of Easter Island, the closest landmass. Salas y Gómez consists of two rocky pinnacles, a smaller one in the west measuring 4 hectares (10.5 acres) in area (270 meters north-south, 200 meters east-west), and a larger one in the east measuring 11 ha (500 meters north-south, 270 meters east-west), which are connected by a narrow isthmus in the north, averaging approximately 30 meters in width. The total area is approximately 15 hectares (0.15 km²), and the total length northwest-southeast is 770 meters. Located at latitude South 26.467 and longitude West 105.467, the uninhabited Isla Salas y Gomez is the easternmost point in the mythical Polynesian Triangle whose other end points rest in Hawai’i and New Zealand (the Chilean Navy has placed a beacon of the island but there is no fixed human presence).

Isla Salas y Gómez and its surrounding waters are a national marine park called Parque Marino Sala y Gómez, with a surface area of 150.000 km2. Along with a recently extended marine park around Easter Island and existing sanctuaries around the Desaventurados chain and Juan Fernandez islands, and in conjunction with international environmental organizations, Chile has worked hard to use its legal authority over the territories to curtail the depletion of fishing stocks, particularly those of the jack mackerel, in the face of increased fishing pressure from predominantly Asian-owned trawling fleets. Extending national maritime parks contiguous to in-shore or island territorial possessions also allows the Chilean Navy to be the primary enforcement agency within them, thereby expanding Chile’s de facto jurisdiction in South Pacific waters.

The Juan Fernandez Islands, 600 kilometers from the mainland, are mainly known for having been the home to the marooned sailor Alexander Selkirk , which may have inspired the Daniel Defoe novel Robinson Crusoe and which have given them the alternative name of Robinson Crusoe islands. The islands have an area of 181 km2 (70 sq mi), of which 93 km2 (36 sq mi) are taken up by Robinson Crusoe island (together with Santa Clara), and 33 km2 (13 sq mi) by Alexander Selkirk island. At the time of the 2002 census the population is 633 (all on Robinson Crusoe), with 598 resident in the capital, San Juan Bautista, and on Cumberland Bay on the north coast of the island. There are both naval and air force installations on the main island, the strength of which is determined by the state of border relations with Peru (since the Juan Fernandez Islands are the closest to the Chile-Peru maritime border).

Political Administration and Military Forces

The Chileans have more than a century of maritime presence far off shore. Their permanent presence in Eastern Island dates to the 1888 annexation and the Chilean Navy administered the island until 1966 (Rapa Nui were only granted Chilean citizenship that year). Similarly, the Juan Fernandez Islands have had a permanent resident population of Chileans dating to the turn of the 20th century, with claims on the Desaventurados and Salas y Gomez island dating to that time. Easter Island shares with Juan Fernandez Islands the constitutional status of “special territory” of Chile, granted in 2007. As of 2011 a special charter for the islands was under discussion in the Chilean Congress. The islands are provinces of the Valparaiso (Fifth) Region and contain a single commune (comuna) equivalent to a municipality. Both the Easter Island province and the commune are called Isla de Pascua and encompass the whole island and its surrounding islets and rocks, plus Isla Salas y Gomez to the east. Easter Island and Juan Fernandez islands belong to the 13th electoral district and 6th senatorial constituency. They are represented in the Chilean Congress by two senators and two deputies each. Although indigenous Rapa Nui sit on the six member Easter Island municipal council and have been represented in the House of Deputies, the municipal bureaucracy, law enforcement and most political positions are predominately occupied by first or second generation mainland Chileans. In addition, the presence of a substantial military garrison in Hanga Roa ensures Santiago’s control over domestic affairs on the island. Inhabitants of the Juan Fernandez islands are predominantly of mainland stock, so internal tensions with indigenous populations do not exist. The over-representation of the Pacific island territories in the Chilean Congress should be noted, with two of seven Senators elected from the Valparaiso district coming from Easter and Juan Fernandez Islands (out of a total of 38 Senators), and two of 12 Valparaiso deputies (out of a total of 120) coming from these underpopulated territories.

The Chilean Navy maintains a 6,600 foot runway facility and skeleton crew on San Felix Island at the otherwise uninhabited Desaventurados Islands. The runway was used by RNAF Nimrod MR2 patrol aircraft during the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas War. The Air Force maintains a 10,000 foot runway on Easter Island that also serves as a commercial airport. A detachment of Navy Marines has a permanent base at Hanga Roa, rotating company-sized detachments on regular deployments. The Navy permanently stations an off-shore patrol vessel in Hanga Roa, and both it and Juan Fernandez are regularly used for naval surface and amphibious exercises, sometimes in conjunction with foreign navies such as that of the US.

The Chilean Navy currently has 68 ships in its inventory, with six on order. These include eight frigates, four submarines (two Scorpene class), seven missile boats, six amphibious warfare ships , sixteen patrol boats, two research vessels and an icebreaker. It has an air wing that includes three P-3 Orions and 21 helicopters as well as other patrol and cargo craft (the Chilean Navy has no air combat wing, which is the Air Force’s responsibility). It participates in a number of bilateral and multilateral naval exercises, including the UNITAS annual exercise with other Western Hemisphere fleets. It is the first Latin American navy to have participated in bi- and multilateral exercises with Asian navies in the Western Pacific, and has regular SAR maneuvers with elements of the French Pacific Fleet. It has a maintenance and service upgrade agreement for its P-3 fleet with New Zealand, as well as a number of bi-lateral service accords with Argentina. The Chilean Air Force conducts regular maritime combat patrols using F-16 AM/BM and C/D, F-5E and A-36 Halcon fixed wing platforms along with a number of rotary vehicles and a Hermes Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). These regularly conduct joint maritime inter-operability training with the Navy alone or in conjunction with multinational exercises.

Chilean maritime strategy is designed to prevent aggression and project force, engage in humanitarian assistance and rescue operations, promote economic growth through sea-borne trade, foster human development in its island possessions and to preserve environmental conditions and natural resources within its Area of Operations (AOR). This is covered by the “3 Vector” strategy that overlaps military, diplomatic and socio-economic objectives in a latticework of operational capabilities that occupy 25,000 uniformed personnel (including 5,500 Marines).

3 Vector Strategy Charts

Reference: Admiral Miguel Vergara, “Presentation,” Report of the Proceedings of the 16th International Seapower Symposium, October 23-26, 2003. Newport, Rhode Island: US Naval War College, 2004: 69-74 (esp. 72-73). Click here for PDF

- Chile-Triconti-Map (full size)

- Chile – Location and size, Territories and dependencies, Climate, Topographic regions, Oceans and seas

- Nationsencyclopedia.com/geography/Afghanistan-to-Comoros/Chile

- Aeroflight.co.uk – AirForce/Chile-af-bases

- USNWC.edu – for Chile, see pp.69-74

- Chiledefense.blogspot.co.nz

- Armada.cl

- Armada.cl Doctrina Maritima (pdf) (Spanish)

- OECD-ilibrary.org – Monthly Statistics of international Trade Volume 2012 Chile

- http://www.armada.cl/prontus_armada/site/edic/base/port/armada_ingles.html